By Zoe Corbyn

This is the sixth feature in a six-part series that is looking at how AI is changing medical research and treatments.

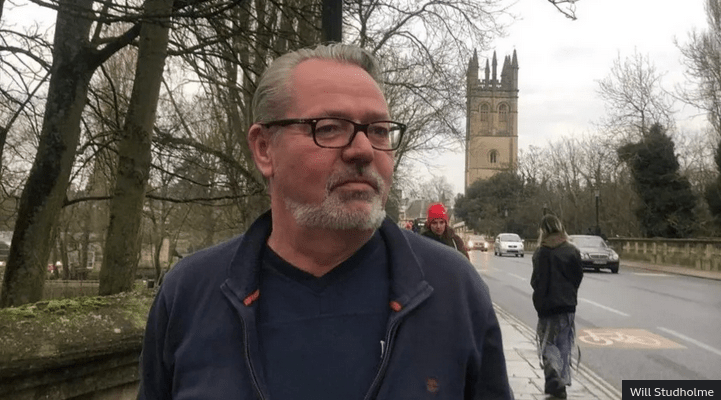

When 58-year-old Will Studholme ended up in accident and emergency at an NHS hospital in Oxford in 2023 with gastrointestinal symptoms, he wasn’t expecting a diagnosis of osteoporosis.

The disease, strongly associated with age, causes bones to become weak and fragile, increasing the risk of fracture.

It turned out that Mr Studholme had a severe case of food poisoning, but early in his ailment’s investigation, he received an abdominal CT scan.

That scan was then later run through artificial intelligence (AI) technology which identified a collapsed vertebra in Mr Studholme’s spine, a common early indicator of osteoporosis.

Further testing ensued, and Mr Studholme emerged not only with his diagnosis, but a simple treatment: an annual infusion of an osteoporosis drug that is expected to improve his bone density.

“I feel very lucky,” says Mr Studholme, “I don’t think this would have been picked up without the AI technology.”

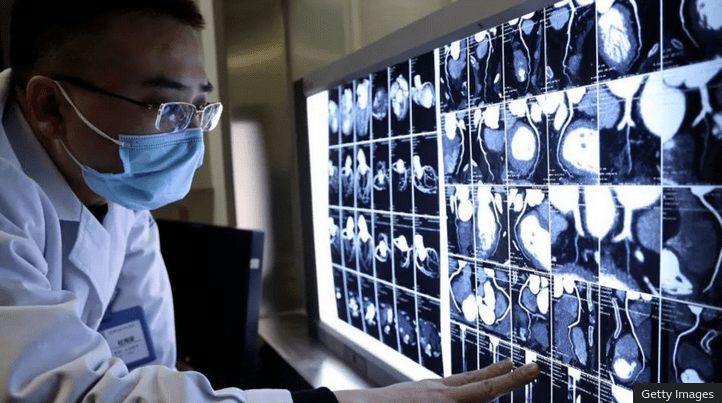

It isn’t unheard of that a radiologist might note something incidental in a patient’s imaging – an undetected tumour, a concern with a particular tissue or organ – outside of what they had originally been checking for.

But applying AI in the background to systematically comb through scans and automatically identify early signs of common preventable chronic diseases that might be brewing – regardless of the reason the scan was originally ordered – is new.

The clinical use of AI for opportunistic screening or opportunistic imaging, as it is called, “is just beginning” notes Perry Pickhardt, a professor of radiology and medical physics at the University of Winconsin-Madison, who is among those developing the algorithms.

It is considered opportunistic because it takes advantage of imaging that has already been done for another clinical purpose – be it suspected cancer, chest infection, appendicitis or belly pain.

It has the potential to catch previously undiagnosed diseases in the early stages, before onset of symptoms, when they are easier to treat or prevent from progressing. “We can avoid a lot of the lack of prevention that we have missed out on previously,” says Prof Pickhardt.

Regular physicals or blood tests often fail to pick up these diseases, he adds.

There’s a lot of data in CT scans related to body tissues and organs that we don’t really use, notes Miriam Bredella, a radiologist at NYU Langone who is also developing algorithms in the field.

And while analysis of it could theoretically be done without AI by radiologists making measurements – it would be time consuming.

There are also benefits of the technology in terms of reducing bias, she notes.

A disease like osteoporosis, for example, is thought of as mostly affecting thin, elderly white women – so doctors don’t always think to look outside of that population.

Opportunistic imaging, on the other hand, doesn’t discriminate that way.

Mr Studholme’s case is a good example. Being relatively young for osteoporosis, male and with no history of broken bones, it is unlikely he would have been diagnosed without AI.

In addition to osteoporosis, AI is being trained to help opportunistically identify heart disease, fatty liver disease, age-related muscle loss and diabetes.

While the main focus is on CT scans, for example of the abdomen or chest, work is taking place to opportunistically glean information from other types of imaging too, including chest x-rays and mammograms.

The algorithms are trained on many thousands of tagged previous scans, and it is important the training data includes scans from a wide swathe of ethnic groups if the technology is going to be deployed on a diverse range of people, stress the experts.

And there is supposed to be a level of human review – if the AI finds something suspect it would be sent to radiologists to confirm before it is then reported on to doctors.

Source: bbc.com