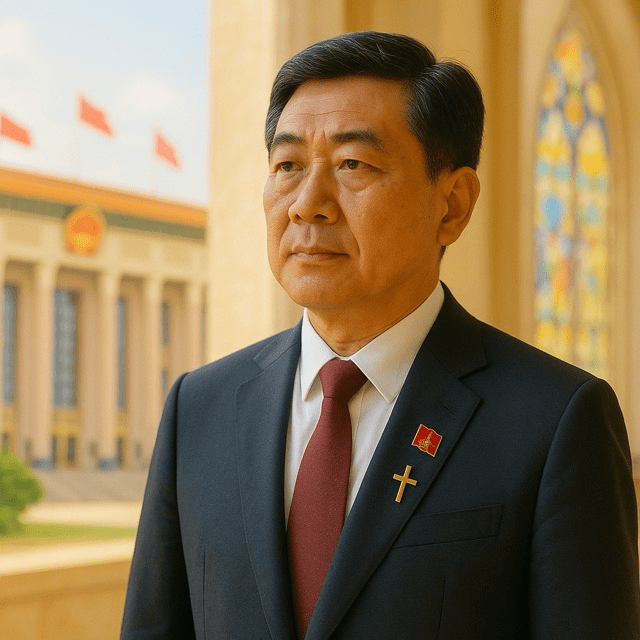

When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) convenes its loftiest gatherings, the scene appears uniformly secular, even militantly atheistic. Yet multiple sources inside the Church in China insist that a small—but symbolically potent—number of Party functionaries have quietly received Christian baptism and now live what veterans of the underground Church call a “double life.” In 2024 the Denver Catholic reported that a growing cohort of new converts includes “well-educated, affluent, and even members of the Communist Party (which technically forbids religious affiliation).” Priests interviewed for that piece said some cadres first encountered Christianity while studying abroad and later sought clandestine instruction once back in China. Baptism normally takes place in homes or in rural chapels after dark, with phones surrendered at the door and the lights kept low—a ritual echo of the Cultural Revolution era, when faith could cost one’s freedom.

Why risk everything? In Beijing, one veteran lay Catholic speaks of a “spiritual vacuum” among technocrats charged with delivering Xi Jinping’s “Common Prosperity.” “They see the slogans every day,” he says, “but the slogans do not answer the heart.” Conversions remain statistically tiny; no more than a few dozen cases are documented each year. Still, their existence undercuts the Party’s claim that religious belief withers as education and income rise. And it explains a paradox Chinese bishops have long observed: some of the most sympathetic local officials assigned to enforce religious regulations turn out, on closer acquaintance, to be irregular Mass-goers themselves.

A New Flashpoint: Bishops Named During the *Sede Vacante*

This subterranean Catholic presence forms the uneasy backdrop to Beijing’s latest act of ecclesial brinkmanship. On 29 April 2025—just days after the death of Pope Francis and with the See of Peter officially sede vacante—the state-controlled Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association “elected” two new bishops: Fr Wu Jianlin as auxiliary in Shanghai and an unnamed cleric for Xinxiang. The investigative magazine Bitter Winter broke the story, stressing that under canon law no bishop can be appointed when the papal throne is vacant. Mainstream outlets quickly confirmed the report; The Sunday Times called the move a “gauntlet for Pope Leo XIV,” noting that Xinxiang already has a Rome-appointed bishop languishing in prison.

By acting during the interregnum, the CCP signaled two things. First, it no longer feels bound by even the letter of the 2018 provisional agreement with the Holy See, which—though secret—entrusted ultimate nominating authority to the pope. Second, Beijing is testing the mettle of the new pontiff from day one. Accepting the ill-timed appointments would ratify a precedent that any future sede vacante constitutes an open season for unilateral ordinations. Rejecting them, on the other hand, could collapse seven years of fragile dialogue.

Why Crypto-Catholics Matter

Enter the Party’s hidden believers. Sources in northern Hebei describe an “unwritten pastoral plan”: if a baptized official is transferred to a new post, the local Church discreetly informs the receiving diocese so that the official can continue to receive the sacraments. These officials, in turn, sometimes moderate the harshest local campaigns—for example, delaying church demolitions until parish records can be removed.

Their fragile leverage depends on remaining invisible; public vigilance campaigns reward citizens for reporting Party members who practice religion. Yet their very existence complicates Beijing’s narrative that Catholicism is a foreign infiltration. Within Zhongnanhai itself, the line between Party and pew is blurrier than propaganda suggests. Sources inside the Vatican and well informed indicate that Xi Jinping’s wife would be a baptized crypto-Catholic.

Scenarios Ahead

Vatican Pushback: If Pope Leo XIV refuses to recognize the Shanghai and Xinxiang “bishops-elect,” Beijing could retaliate by intensifying pressure on underground clergy—and on crypto-Catholic officials whose baptismal status makes them politically vulnerable.

Quiet Bargain: Rome may delay a formal verdict while negotiating a face-saving formula (e.g., “administrators” rather than bishops). Crypto-Catholic cadres could become informal channels, urging restraint from within the bureaucracy.

Open Confrontation: Should the Holy See publicly denounce the appointments, the CCP might expose or purge suspected believers in its own ranks to prove ideological purity—an outcome local clergy fear most.

The Stakes for Religious Freedom

For decades China’s underground Church survived because ordinary believers—including some apparatchiks—were willing to whisper Credo behind closed doors. Today those whispers reach the Vatican in real time via encrypted apps, urging Rome not to capitulate. Whether Pope Leo XIV can honor that plea without closing the last diplomatic door remains the defining test of his first year.

What is clear is that the drama now unfolding is not simply a tug-of-war between two institutions. It is also the story of men and women in the corridors of Party power who, against every ideological expectation, have passed through the waters of baptism—and discovered that conscience can be as subversive as any manifesto.