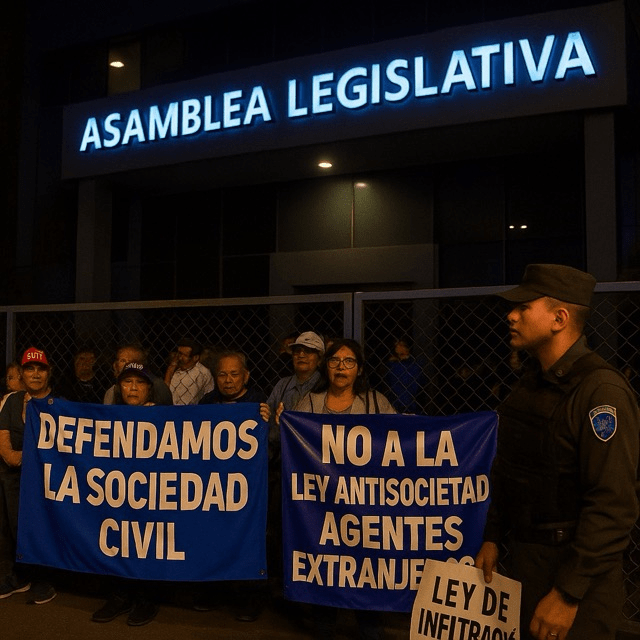

Legislative Assembly passes 30 % tax on foreign donations and sweeping controls despite warnings from civil society and Washington

San Salvador — In a late‑night session on 20 May 2025, El Salvador’s Legislative Assembly, dominated by President Nayib Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas party, approved a law that imposes a 30 percent tax on all funds sent from abroad to Salvadoran non‑governmental organizations (NGOs).¹ The “Foreign Agents Law,” passed with 57 votes in favor and three against, also requires NGOs to register under a new government‑run ‘Registry of External Cooperation’ and to detail how every foreign dollar is spent.

Lawmakers framed the measure as a bulwark against what they called “opaque political agendas financed from overseas.” “This closes a legal loophole and defends our sovereignty,” said vice‑president of the Assembly Suecy Callejas during debate. Supporters insist revenues from the tax will finance social programs, though the legislation contains no earmark clause specifying how funds will be allocated.²

Opposition deputies from the centrist Nuestro Tiempo and left‑leaning FMLN parties warned that the bill weaponises taxation to starve watchdog groups that document human‑rights abuses and government corruption. “You are placing a fiscal guillotine over civil society,” said FMLN legislator Anabel Belloso before abandoning the chamber in protest.³

The law revives and expands a 2021 ‘foreign agents’ proposal that Bukele shelved after U.S. and EU pressure. Under the new version, NGOs that fail to register or pay the tax face fines of up to US $200,000 and possible asset seizures. It also prohibits organizations from receiving anonymous donations, altering project goals without prior approval, or engaging in unspecified ‘political propaganda.’⁴

Bukele, who celebrated a landslide re‑election in February under an extended state of emergency, hailed the vote in a midnight social‑media post: “We will not let foreign money destabilize our country.” Critics counter that the real target is the dwindling handful of groups still willing to challenge the president’s iron‑fisted security policies, which have jailed more than 80,000 Salvadorans in three years.

International condemnation was swift. Amnesty International said the law “deepens El Salvador’s slide into authoritarianism” and violates the right to freedom of association.⁵ Human Rights Watch urged foreign donors to explore “creative channels” to bypass the tax and keep humanitarian aid flowing. The U.S. State Department called the legislation “counter‑productive” and hinted at a review of bilateral assistance.

More than 400 local organizations—from environmental defenders to women’s‑rights shelters—signed a joint declaration predicting layoffs and program shutdowns within months. “Our budgets already stretch every cent,” said Ana María Campos of the NGO Cristosal. “A 30 per cent cut means fewer legal clinics, fewer scholarships, fewer meals for displaced families.”

Analysts see the law as part of a regional trend: Nicaragua, Guatemala and Honduras have all enacted statutes restricting foreign‑funded NGOs since 2020. “Central America’s rulers are borrowing pages from the same playbook: label critics as foreign proxies, then regulate them out of existence,” said Kevin Quintanilla, a researcher at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington.

Yet some Salvadorans back the measure. A CID‑Gallup poll this week found 55 % agree that NGOs should disclose funding sources, though only 29 % support the 30 % tax. Business associations applauded the registry provision but urged Congress to slash the levy to 5 %.

The law takes effect eight days after publication in the Official Gazette, leaving NGOs scrambling to decipher its 42 articles and potential loopholes. Legal advisers are debating whether humanitarian aid delivered in kind—such as medical supplies—will be taxed at declaration value or exempt. The Finance Ministry promised clarifying regulations “within 60 days,” but many organizations fear the ambiguity is deliberate.

With Bukele’s super‑majority secure until at least 2027, civil‑society leaders acknowledge that judicial reversal is unlikely. Their immediate hope is diplomatic leverage: the EU is reviewing €110 million in governance grants, while the Millennium Challenge Corporation has warned that rule‑of‑law setbacks could affect a pending US $460 million compact. If the pressure fails, Salvadoran NGOs may face a stark choice: comply, relocate operations abroad—or close their doors entirely.