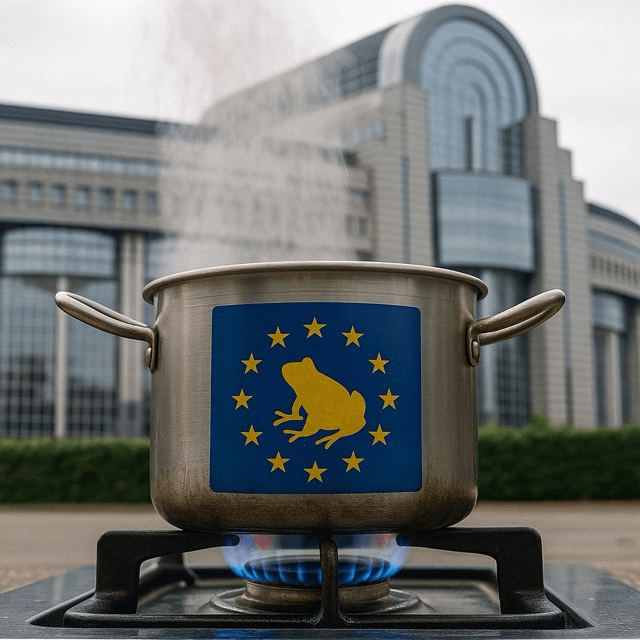

Why Europe’s indifference to Mario Draghi’s competitiveness blueprint could leave the EU slowly stewing in strategic decline

Introduction

Mario Draghi—Italy’s former prime minister, Euro‑saviour at the European Central Bank and one of the bloc’s most persuasive crisis managers—was commissioned in late 2024 by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to draft a sweeping plan for European competitiveness. His interim findings warn that the single market is losing ground in six critical areas: green tech, artificial intelligence, energy security, capital markets, defence, and raw‑materials access. Yet six months later, the 27 capitals appear less galvanised than gnarled by competing national agendas. The risk, Draghi has hinted in closed‑door briefings, is that Europe imitates the proverbial frog placed in cool water: unaware of the slow boil until escape is impossible.

1. The Draghi Plan in a Nutshell

Leaked drafts propose a €500 billion ‘Sovereignty Fund’ financed by joint bonds, aimed at turbo‑charging R&D, scaling battery and semiconductor supply chains and accelerating defence integration. Draghi’s team also sketches out an EU‑wide capital‑markets union to unlock €3 trillion in private savings for strategic investment. Underpinning it all: a simplified state‑aid regime to match U.S. Inflation Reduction Act subsidies and a fast‑track permitting scheme for renewables. In other words, Draghi offers Brussels the bones of an industrial policy that could prevent talent and factories from drifting across the Atlantic or, worse, East toward low‑cost autocracies.

2. Brussels Shrugs—Why?

In theory, few contest the urgency. In practice, finance ministers from the ‘Frugal Four’—the Netherlands, Sweden, Denmark and Austria—balk at mutualised debt. Berlin, wrestling with a constitutional court ruling that blows a €60 billion hole in its energy‑transition fund, is reluctant to sign new cheques. Paris wants looser state‑aid rules but resists deeper capital‑markets integration that could threaten its banking champions. Smaller Eastern members fear a raw deal unless cohesion funds are ring‑fenced. The net result: council conclusions full of warm words but no commitment beyond ‘further reflection’—Eurocrat code for kicking the can.

3. Warning Lights on the Dashboard

The costs of delay are already visible. Euro area GDP growth is forecast at just 0.7 percent this year, half that of the United States. European solar‑panel firms complain that Chinese imports undercut prices by 35 percent. Venture‑capital investment in EU tech start‑ups fell 38 percent in 2024 compared with a 2 percent dip in the U.S. Meanwhile, defence stocks have rallied, but member‑state procurement remains fragmented—22 different armoured‑vehicle programs, 16 tank models and at least seven drone platforms. Every divergence is another degree in the warming pot.

4. The Boiled Frog Metaphor Made Flesh

The danger is not sudden catastrophe but incremental erosion. Energy‑price volatility chips away at heavy‑industry margins; regulatory divergence nudges start‑ups to Delaware; demographic stagnation saps the labour force. Like the frog, Europe adapts to each new temperature—until the cumulative heat becomes lethal. Draghi’s plan aims to flip the metaphor: a short, sharp shock of fiscal firepower and rule‑streamlining that forces adaptation before it’s too late.

5. Political Inertia and Fragmented Mandates

Unlike the euro‑crisis bazooka Draghi once wielded at the ECB, this blueprint lacks a single pressure point. Competitiveness straddles energy, trade, education and digital portfolios—each guarded by different commissioners and ministerial councils. Upcoming elections—European Parliament in 2029, national contests in France, Poland, and the Netherlands—encourage leaders to hoard industrial spoils rather than pool them. The pandemic showed Europe can act boldly (see: NextGenerationEU), but that required an existential jolt. Today’s warnings, by contrast, are statistical and strategic—harder to translate into street‑level urgency.

6. What Happens Next?

Commission officials say the final Draghi report will land before the December European Council. Even if leaders endorse the analysis, financing mechanisms could languish until the next multi‑annual budget talks in 2027. Draghi allies fear that by then the ‘American vortex’—massive U.S. clean‑tech subsidies plus soaring defence orders—will have sucked away Europe’s most scalable innovators. The ECB can stabilise bonds, but it cannot print skilled engineers or critical minerals. Nor can it legislate the political will to move before the water boils.

Conclusion

Europe’s founders liked to say the Union advances on the back of crises. Draghi’s diagnosis is that the current one is slow‑burn and structural, lacking the drama that normally triggers institutional leap. If the bloc ignores his prescription, it risks illustrating a darker parable: that a creature can be boiled not by malice or negligence alone, but by comfort with incremental decline. The question for Brussels is straightforward: jump now, or accept the fate of the boiled frog.