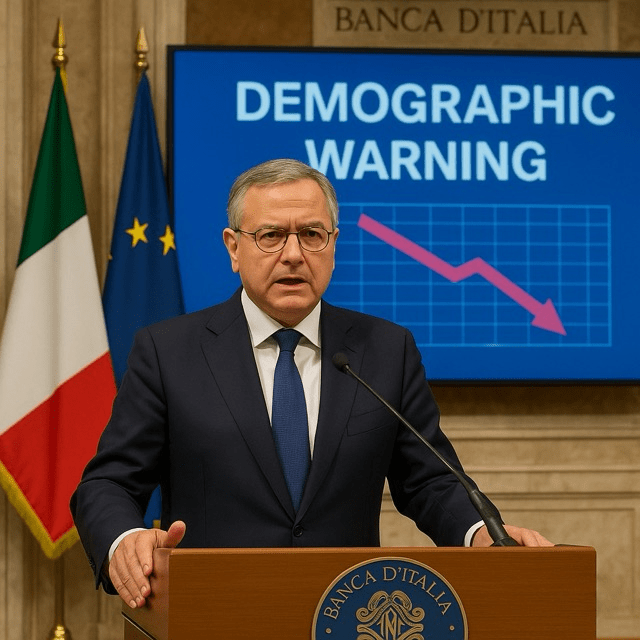

The Bank of Italy governor warns that an ageing nation, a brain‑drain, and sky‑high debt could erode GDP by double digits within fifteen years

Rome, 30 May 2025 — In his first set of *Concluding Remarks* as Governor of the Bank of Italy, Fabio Panetta issued what may be the starkest macro‑economic warning heard in Via Nazionale since the euro‑crisis era. Demographic decline, he argued, is no longer a slow‑burn structural problem; it is “a clear and present threat” that could shrink Italy’s potential output by 11 percent by 2040 unless immediate action is taken.

Panetta painted the picture with hard numbers. According to new estimates released alongside the central bank’s Annual Report, 156,000 Italians emigrated in 2024—a 36.5 percent jump from the previous year—pushing total outward migration to its highest level in twenty‑five years (Financial Times, 31 May 2025). Over the past decade more than one million citizens, most of them university‑educated and under 35, have left the country; only half have returned. Real wages in Italy have been flat since 2000, he noted, fuelling a “vicious circle” in which talent flight begets low productivity growth, which in turn suppresses wages further.

Ageing compounds the problem. In remarks later amplified by the ANSA news agency, the governor stressed that Italy’s median age—already the second‑highest in the EU—will rise from 48 today to 53 by 2040. “The working‑age population is likely to fall by almost 4 million people in the next fifteen years,” he said, adding that the old‑age dependency ratio could jump to 44 percent, up from 36 percent today. “An economy cannot prosper if its young people see future prosperity elsewhere.”

Panetta’s prescription blends labour‑market reform with immigration and family policy. He urged Parliament to target female participation rates “commensurate with northern‑European peers,” accelerate digitalisation in small firms, and introduce tax credits for employers that convert fixed‑term contracts into permanent ones. Crucially, he broke with some members of the current governing coalition by calling for “managed, legal immigration” to offset labour shortages in construction, hospitality, and elder care.

Debt also loomed large. Italy’s debt‑to‑GDP ratio, at 137 percent, is the second‑highest in the eurozone after Greece. “Lowering that ratio is not merely an accounting exercise; it is the pre‑condition for funding demographic adaptation,” Panetta said, echoing lines from the written text of his speech hosted on *Banca d’Italia’s* website. He urged the government to use expected interest‑savings from disinflation to trim deficits rather than expand current spending, warning that “financial markets have short memories but long spreadsheets.”

The demographic alarm comes just as inflation—headline and core—appears largely tamed. In a separate Bloomberg interview following the release of the Annual Report, Panetta noted that “disinflation has not taken too high a toll on the economy and is now close to completion.” Yet he cautioned that the European Central Bank’s room for additional rate cuts “has naturally diminished” (Bloomberg, 30 May 2025), adding that volatile U.S. trade policy calls for “pragmatism and flexibility” (Reuters, 31 March 2025).

Financial markets responded nervously to the demographic‑debt linkage. Italian BTP yields initially widened by eight basis points against Bunds before retracing after the Treasury reaffirmed a primary‑surplus target for 2026. Analysts at UniCredit wrote that Panetta’s speech “raises the bar for fiscal discipline at exactly the moment Rome prepares its 2026 budget.” Meanwhile the European Commission privately welcomed the intervention, according to an official briefed on the matter, seeing it as cover for tougher enforcement of the re‑vamped Stability Pact.

Political reaction was mixed. Economy Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti conceded that “the numbers on ageing are crystal clear,” but pushed back on migration, arguing that “Italy must first tap the potential of its own youth.” Opposition leader Elly Schlein said the speech exposed the government’s “empty slogans on family policy,” noting that childcare coverage still lags the EU average by ten percentage points. Employers’ federation Confindustria endorsed Panetta’s tax‑credit proposal but said a genuine growth plan must also slash red tape surrounding renewable‑energy permits.

Panetta’s emphasis on human capital fits a broader trend among central bankers who increasingly weigh demographic dynamics alongside inflation and financial stability. Bank of Japan Governor Kazuo Ueda has made similar arguments, while Bundesbank President Joachim Nagel last month warned that Germany faces a “demographic cliff” absent further immigration. Yet Italy’s situation is unique in the euro area for combining rapid population ageing with a persistently high debt ratio and decades‑long productivity stagnation.

What happens next lies partly outside Via Nazionale. The February 2025 labour‑reform bill, still in committee, could raise female participation by two percentage points if enacted. A promised family‑benefit top‑up worth €4 billion annually is due in the autumn budget. But Panetta warned that fiscal incentives alone will not suffice without “a social compact that convinces young Italians that their future can unfold at home.” His closing words—“Time is a non‑renewable resource; let us not waste it”—echoed in the parliamentary corridors long after reporters filed their stories.

Whether Italy’s political class turns the governor’s alarm into policy remains to be seen. For now, Fabio Panetta stands as both messenger and metronome, counting down the years until demographic arithmetic overwhelms economic wishes. The tick‑tock he hears is not a market clock but a demographic one—and it is getting louder.