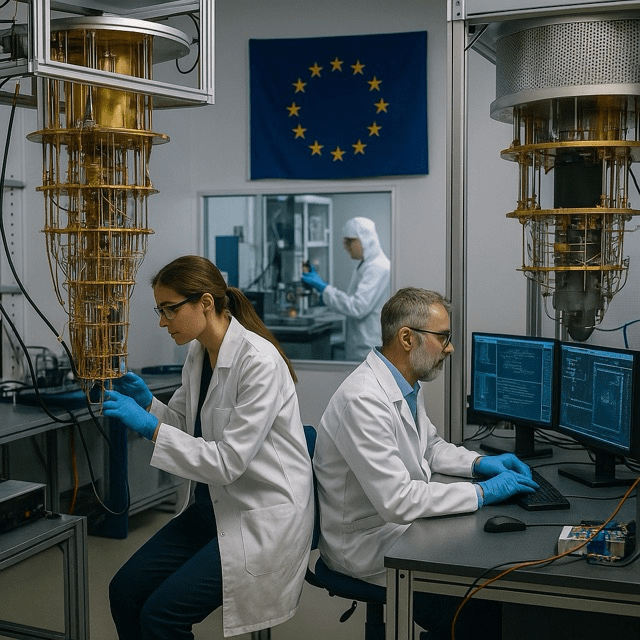

EU to pool funding and expertise in quantum computing to build a competitive ecosystem and reduce dependence on the US

Brussels is setting the stage for what could be the most ambitious scientific collaboration in Europe’s recent history. Faced with the realisation that quantum computing has the potential to revolutionize industries from finance to pharmaceuticals, EU leaders have drafted a plan to pool national funding and research capabilities. The goal is clear: to construct a homegrown quantum ecosystem robust enough to rival offerings from the United States and China. As the United States announces multibillion-dollar investments under its National Quantum Initiative, European policymakers fear they risk falling behind unless they unite.

At the heart of Brussels’ strategy is the creation of a centralized funding mechanism under the auspices of Horizon Europe, the EU’s flagship research and innovation program. Instead of fragmented grants disbursed by individual member states, this mechanism will allocate resources based on competitive proposals that demonstrate cross-border collaboration. By doing so, Brussels hopes to leverage economies of scale, ensure critical mass in key research areas—such as superconducting qubits and topological materials—and foster an integrated supply chain encompassing hardware, software, and talent development.

Several national champions are already on board. France’s CEA–Leti and Germany’s Fraunhofer Society have agreed to coordinate their cleanroom facilities, while the Netherlands’ QuTech institute will lead work on quantum internet protocols. Smaller member states with niche specialisations—such as Italy’s expertise in cryogenics and Spain’s strengths in photonic chips—will be invited to contribute, ensuring that no region is left on the sidelines. This distributed model aims to balance excellence with inclusiveness, preventing the concentration of all activities in a handful of countries.

Experts note that Europe’s approach contrasts sharply with the U.S. model, which favours large federal contracts awarded to a few industry consortia. By contrast, Brussels emphasizes open science, public-private partnerships, and interoperability standards. The European Commission has proposed a governance structure that includes representatives from industry, academia, and member states, tasked with aligning roadmaps, managing intellectual property rights, and safeguarding ethical standards. Observers predict that such an arrangement could accelerate commercialization while maintaining Europe’s tradition of regulation and transparency.

The proposed budget for the quantum flagship initiative is €3.5 billion over five years, with an additional €2 billion expected from national cofunders. These figures, though substantial, still lag behind the U.S. federal commitment of over US$4.5 billion for the same period. Brussels officials argue that Europe’s advantage lies in its diverse research base and existing industrial clusters. They also point to the European Investment Bank, which may offer favorable loans and equity financing to promising startups emerging from publicly funded labs.

However, challenges remain. Coordinating dozens of institutions across multiple legal frameworks is notoriously difficult. Previous attempts at pan-European projects—such as the Galileo satellite navigation system—have encountered delays and cost overruns. Moreover, the sensitive nature of quantum technologies, many with potential military applications, raises security concerns. Member states will need to agree on export controls, cybersecurity measures, and protocols to prevent espionage—an added layer of complexity that Brussels must navigate carefully.

Private industry is watching closely. Major players like Airbus, Siemens, and Thales have already partnered with research consortia, seeking early access to quantum-enhanced algorithms for encryption and materials discovery. Venture capital firms are warming up to European startups such as Pasqal in France and IQM in Finland, which have demonstrated promising prototypes. Yet investors caution that timelines for achieving quantum advantage—where quantum machines outperform classical supercomputers—remain uncertain, with optimistic estimates placing breakthroughs anywhere between five and ten years away.

Talent retention may prove equally critical. While Europe benefits from top-tier physics departments—in Oxford, ETH Zurich, and Delft—many leading researchers have emigrated to the U.S., drawn by lucrative positions and abundant funding. Brussels’ plan includes generous scholar grants, “quantum fellowships,” and mobility programs designed to reverse the brain drain. If successful, these measures could cultivate a generation of European quantum scientists committed to homegrown innovation rather than overseas offers.

As the initiative moves from drawing board to implementation, timing will be crucial. The European Parliament is expected to vote on the funding proposal in the autumn, with member states required to ratify contributions shortly thereafter. Pilot projects in quantum communication networks are slated to begin within 12 months, alongside joint procurement of standardized cryogenic hardware. Brussels will closely monitor progress, with quarterly reviews to assess milestones and reallocate resources if necessary.

Brussels’ quantum gamble represents more than a scientific endeavour: it is a bid for technological sovereignty. By reducing reliance on U.S. technology and supply chains, Europe aims to assert its strategic autonomy in an era of geopolitical competition. Whether this grand experiment will yield a competitive quantum ecosystem or succumb to bureaucratic inertia remains to be seen. For now, the race is on—and Europe is no longer content to sit on the sidelines.