In response to mounting trade pressures from Washington, Ottawa pivots toward maximizing energy exports to shield its economy.

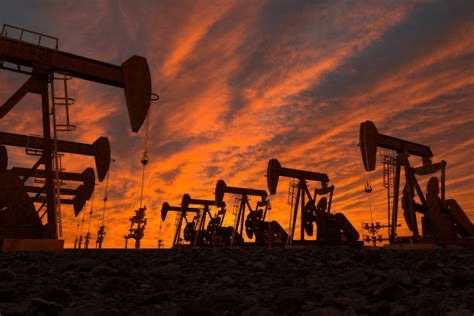

Faced with a new wave of protectionist trade measures from the United States, the Canadian government is preparing to lean into one of its most abundant resources: fossil fuels. In a controversial move, Ottawa is exploring plans to ramp up oil and natural gas production as part of a broader economic strategy to offset the potential damage of U.S. tariffs.

The shift, revealed in briefing documents and confirmed by sources close to the federal cabinet, marks a significant departure from Canada’s recent emphasis on clean energy transition. While officials insist climate targets remain intact, they also acknowledge the need to shield the country’s economy from external shocks — particularly those originating from its largest trading partner.

“With the U.S. imposing or threatening new tariffs on Canadian goods, we have to make use of the leverage we have,” said a senior government adviser. “And one of those is energy.”

Canada holds the world’s third-largest proven oil reserves, much of it locked in Alberta’s oil sands. With global energy demand still high and geopolitical uncertainties driving market volatility, the Trudeau government sees fossil fuel exports as a way to bolster national revenues, protect jobs, and preserve economic stability.

The United States, which remains Canada’s largest energy customer, has not yet targeted oil or gas imports in its tariff discussions. However, Canadian officials fear that broader trade friction — including disputes over lumber, steel, and electric vehicles — could escalate unpredictably.

To preempt economic fallout, Ottawa is weighing new incentives for fossil fuel production and export infrastructure, including LNG terminals in British Columbia and expanded pipeline capacity to the Atlantic coast.

Critics warn that the strategy risks undermining Canada’s climate credibility. Environmental groups have blasted the move, accusing the government of backsliding under pressure.

“This is a dangerous pivot,” said Tara Singh, director of the Green Tomorrow Coalition. “At a time when the world needs leadership on decarbonization, Canada is doubling down on the very industries driving climate change.”

Government sources argue that the measures are temporary and tactical, designed to provide fiscal breathing room as the global economy rebalances. Some analysts suggest Ottawa may be using energy policy as leverage in trade negotiations — offering energy security in exchange for tariff exemptions.

“This could be part of a bigger chessboard,” said Jean-Luc Tremblay, a trade economist at Université de Montréal. “By ramping up energy exports, Canada strengthens its bargaining position with both Washington and other global partners.”

Public opinion remains divided. In oil-producing provinces like Alberta and Saskatchewan, the proposal has been met with applause. In urban centers and among younger voters, however, there is concern that the plan contradicts the government’s stated climate commitments.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has so far walked a careful line, reiterating Canada’s net-zero goals while also defending the importance of “economic resilience.”

The government is expected to release more detailed policy outlines in the coming weeks. Meanwhile, tensions with Washington — and the global demand for energy — show no signs of easing.

As Canada navigates this delicate balancing act, the question remains: can a country be both a climate leader and an energy exporter in a time of rising geopolitical risk?