As tensions simmer in the Great Lakes region, Washington steps in to mediate — but critics question whether peace can last when profits come first.

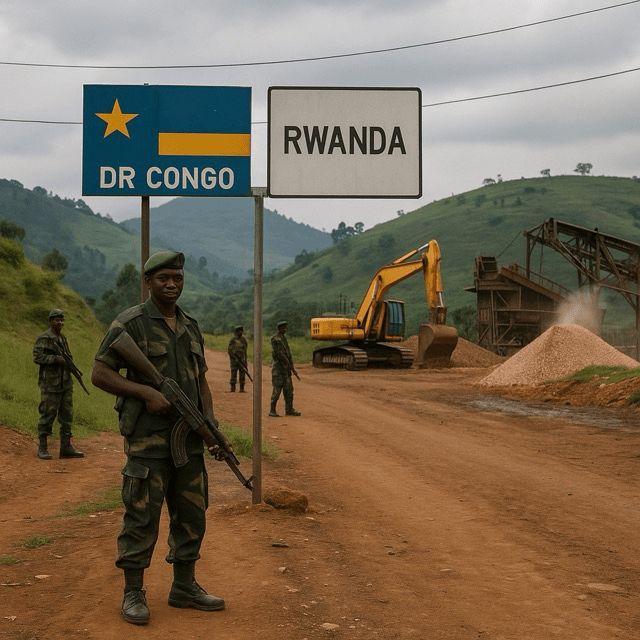

A tenuous calm hangs over the eastern borderlands of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Rwanda, where a recent U.S.-brokered diplomatic push has paused — but not resolved — one of Africa’s most volatile conflicts. Though framed as a step toward regional peace, analysts argue that Washington’s true motivation lies deep underground, in the mineral-rich hills of eastern Congo.

The renewed mediation effort, led by U.S. Special Envoy for the Great Lakes Region, Ambassador Michael Hammer, has brought both Kigali and Kinshasa back to the table. The goal: to de-escalate fighting between Congolese forces and the M23 rebel group, which the DRC accuses Rwanda of backing — a claim Rwanda continues to deny.

The temporary ceasefire has calmed recent flare-ups around North Kivu, but few believe lasting peace is at hand.

“This isn’t a peace agreement — it’s a pause, and one rooted in economic calculus, not justice or reconciliation,” said Jean-Baptiste Kalume, a Congolese human rights advocate based in Goma.

Eastern Congo holds some of the world’s richest deposits of cobalt, coltan, gold, and other critical minerals essential for smartphones, electric vehicles, and renewable energy technologies. With global supply chains increasingly vulnerable and the green transition accelerating, U.S. officials have grown more focused on securing access to these materials.

“The Biden administration sees Congolese minerals not just as a commercial asset, but as a strategic imperative,” said Emily Crawford, an analyst at the Center for Strategic Resources. “Stability in the region directly supports U.S. energy and manufacturing policy.”

Behind the scenes, American diplomats have been pushing for joint mining ventures, improved transparency in mineral certification, and enhanced security for logistics corridors through Rwanda. These economic interests have added urgency — and raised eyebrows.

Critics warn that prioritizing stability for resource extraction risks sidelining deeper issues: local grievances, the role of armed groups, historical animosities, and the lack of accountability for past atrocities.

“Peace built on mineral pipelines is not peace for the people,” said Father Emmanuel Bisimwa, a Catholic priest who works with displaced families in Ituri. “Until the violence at the community level is addressed, this is a house of cards.”

Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame and Congo’s President Félix Tshisekedi have remained publicly cordial in recent weeks, but mutual distrust persists. Congo has stepped up border security and continues to call for international sanctions against Rwanda. Meanwhile, Rwandan forces remain on high alert, accusing Congo of harboring anti-Kigali militias.

International observers from the African Union and the UN have welcomed the pause in hostilities but remain cautious. Past efforts at mediation, including the 2013 Addis Ababa Framework Agreement, have failed to deliver long-term peace.

Washington’s role has drawn both praise and skepticism. While some applaud renewed U.S. engagement in African diplomacy, others note that without robust conflict-resolution mechanisms, the current strategy risks repeating a familiar pattern: extract resources first, worry about peace later.

For now, the people of eastern Congo wait — not for speeches in Brussels or Washington, but for silence at night, for the absence of gunfire, for the safe return of loved ones.

Whether this fragile peace holds will depend not only on minerals and geopolitics, but on the willingness of all actors to prioritize humanity over profit.