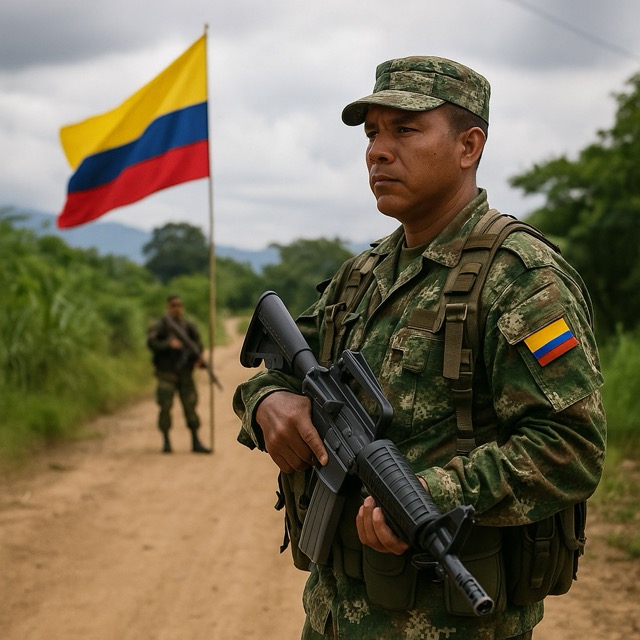

Despite peace accords and international support, Colombia remains locked in a complex web of guerrilla insurgency, paramilitary violence, and narco-driven warfare.

BOGOTÁ – Nearly a decade after the historic 2016 peace accord between the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country is still engulfed in overlapping non-international armed conflicts (NIACs). The shadow of violence lingers across rural territories, fueled by ideological remnants, paramilitary resurgence, and the persistent influence of organized crime.

In regions like Arauca, Cauca, and Norte de Santander, daily life is marred by armed clashes, forced displacement, and insecurity. According to the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law, Colombia is currently experiencing three simultaneous NIACs: involving leftist guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitary successors, and powerful narcotrafficking organizations.

Remnants of the FARC—now fractured into dissident factions—have filled power vacuums left by the demobilized main group. These factions, often loosely coordinated, reject the peace agreement and continue to battle for control over drug-producing territories and strategic corridors.

Meanwhile, right-wing paramilitary groups—many rebranded or operating under new names—remain deeply entrenched. Though officially demobilized in the mid-2000s, these organizations have splintered into what Colombian authorities term ‘criminal bands’ or BACRIM. They act as both mercenaries and drug traffickers, asserting control through brutal tactics, particularly in Afro-Colombian and Indigenous territories.

‘What we’re witnessing is not the return of war—it never left,’ says Maria Camila Restrepo, a human rights observer based in Medellín. ‘The faces have changed, but the underlying dynamics of armed control and terror remain largely the same.’

Complicating the landscape is the role of transnational drug cartels, who finance and exploit both guerrilla and paramilitary actors. Coca cultivation has surged in recent years, turning Colombia into the world’s leading cocaine producer once again. Criminal groups use violence to secure production routes, eliminate competitors, and extort local populations.

The Petro government has attempted a new ‘Total Peace’ initiative, seeking dialogue with all armed actors, including dissident rebels and crime syndicates. Yet implementation has faced setbacks, with ceasefire violations and a lack of centralized authority among non-state actors.

‘Peacebuilding in Colombia is like stitching a wound that keeps reopening,’ notes Jorge Barrios, a conflict analyst at Bogotá’s Universidad de los Andes. ‘You can’t negotiate effectively with factions that have no unified command, no real political ideology, and whose motives are increasingly economic.’

Civilians bear the brunt of the violence. UNHCR reports that over 100,000 Colombians have been forcibly displaced in the last 12 months. Social leaders, land defenders, and journalists are often targeted. Impunity remains high, with many regions effectively outside the reach of state justice.

International observers warn that Colombia’s situation, while no longer dominating headlines, remains one of the most complex and underreported armed conflicts in the Western Hemisphere. The convergence of political insurgency, paramilitary power, and narcotics wealth creates a combustible mix unlikely to be resolved through traditional peace frameworks.

Despite it all, pockets of resilience persist. Local peace initiatives, Indigenous guard units, and NGOs continue working to build stability and preserve community structures. But without sustained political will and comprehensive rural development, experts caution, Colombia’s overlapping wars will remain unresolved.

As July 2025 unfolds, the question for Colombia is not whether conflict continues—but whether the world will continue to look away.