By Sarkis Darbinyan — RKS Global Co-Founder Warns of a Dangerous Shift in Internet Rights

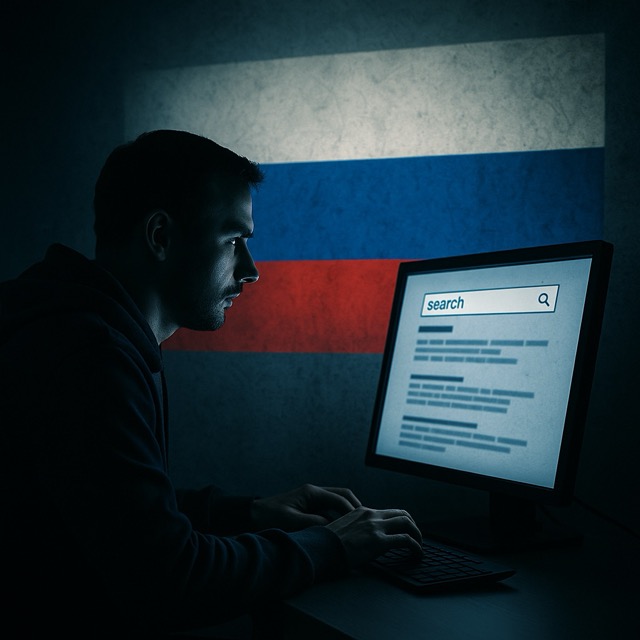

Moscow. In a troubling escalation of state censorship, Russia has moved to criminalise online searches deemed “extremist” or “undesirable,” marking a dangerous new phase in digital repression. Sarkis Darbinyan, co-founder of the digital rights organization RKS Global, warns that these measures not only chill free expression but also undermine fundamental privacy protections for millions of internet users.

Under a law enacted in July, users searching for keywords flagged by the authorities may face fines, detention, or even criminal charges. Websites and search engines are required to implement automated filters, with failure to comply punishable by hefty financial sanctions or suspension of services. Darbinyan describes the policy as “a blunt instrument that entrusts opaque algorithms with life-altering judgments.”

Digital rights advocates note that the list of prohibited terms has grown steadily, encompassing not only calls for violence but also neutral or academic references to political dissent, human rights, and independent journalism. “What was once a tool for countering terrorism is now being repurposed to silence any voice that challenges the state narrative,” Darbinyan writes.

The law’s vague definitions grant security agencies wide latitude to label content as extremist. Darbinyan warns that private browsing is no longer safe: “Even historical or scholarly research on prohibited topics can land you in trouble. The effect is self-censorship, as users avoid search queries that might draw the attention of the security services.”

Search providers operating in Russia face a difficult choice: deploy invasive monitoring tools or withdraw from the market. Some smaller platforms have already announced plans to branch their operations overseas, citing the impossibility of safeguarding user data under the new legal regime.

The consequences extend beyond individual freedoms. Businesses reliant on open access to information—such as researchers, journalists, and technology startups—are reporting declines in productivity and rising compliance costs. “Innovation thrives on the free flow of ideas,” Darbinyan notes, “but when queries become surveilled, creativity is stifled.”

International observers have condemned the law as a violation of Russia’s commitments under the Council of Europe’s human rights conventions. Yet the Kremlin defends the policy as necessary to protect national security and social stability, pointing to alleged foreign interference in domestic affairs.

Civil society groups are exploring legal challenges, but face an uphill battle within a system that consistently tilts in favor of state power. Darbinyan advocates for robust encryption tools and decentralized networks as technical countermeasures, but emphasizes that technological fixes alone cannot substitute for political reform.

As Russia’s internet rights landscape darkens, Darbinyan calls on the global community to support digital defenders. “Solidarity matters,” he writes. “International pressure and cross-border cooperation can help preserve pockets of free expression and protect those who dare to search for the truth.”

With digital repression entering uncharted territory, the stakes could not be higher. For a generation growing up online, the right to seek knowledge and engage in open discourse is under direct attack. The law’s real legacy may lie in whether it silences dissent or ultimately galvanizes a new wave of digital resistance.