The iPhone maker vows to supercharge U.S. manufacturing — but how much is new money, and what really counts as “manufacturing”?

SAN FRANCISCO Apple has lifted its headline commitment to invest in the United States to $600 billion over the next four years, attaching a marquee figure to a sprawling mix of spending that ranges from semiconductor supply chains to data centers, research labs and Hollywood‑style productions. The pledge — unveiled in Washington this week alongside President Donald Trump — adds $100 billion to a $500 billion plan the company laid out earlier this year and instantly reignites a perennial question: how big is Apple’s ‘made in America’ push in practice, and how much of it was coming anyway?

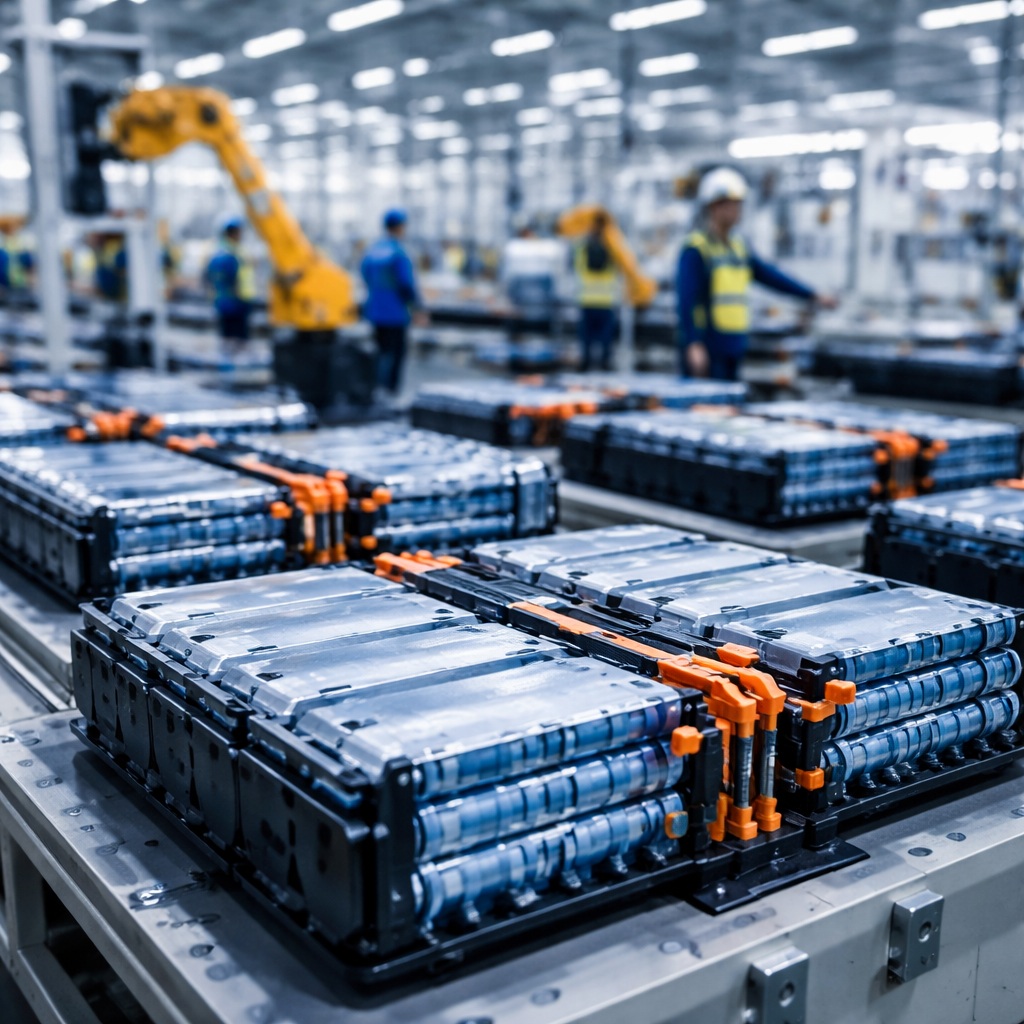

Executives describe the package as a bid to accelerate an “end‑to‑end” domestic pipeline for key components, particularly chips, and to reduce exposure to geopolitical risk. In parallel, Apple is promoting a new American Manufacturing Program intended to nudge suppliers to expand on U.S. soil. Much of the early attention has focused on Texas, where wafer maker GlobalWafers is ramping in Sherman, Texas Instruments is installing new tools, and equipment giant Applied Materials and Samsung are expanding chip‑related operations in the Austin area — all pieces that plug into Apple’s devices and services.

But the fine print suggests the $600 billion wraps together very different buckets of activity. In Apple’s own framing, the total includes multi‑year U.S. procurement from suppliers, domestic capital expenditures such as data centers, and R&D spending — along with grants and long‑term contracts aimed at luring partners to manufacture core components stateside. Some categories clearly advance manufacturing capacity; others, like cloud infrastructure or content spending, are important to Apple’s business but only tangentially tied to factory output. The company has not provided a line‑item breakdown of what counts toward the total.

That ambiguity matters because the headline number risks being confused with plant‑by‑plant investment. Several suppliers in Apple’s orbit — including TSMC and Texas Instruments — already had large U.S. projects under way, financed from their own balance sheets. When Apple signs long‑term offtake deals or co‑funds tools, what portion should be attributed to Cupertino versus to the supplier’s previously announced capex? Analysts say the answer will vary deal by deal, which makes auditing the $600 billion difficult and fosters accusations that the pledge is as much politics as economics.

At the center of the political calculus are trade barriers. The White House has paired carrots for companies that deepen U.S. production with new tariff threats on imported semiconductors and electronics. Apple’s executives have strong incentives to show they are localizing critical inputs to shield the iPhone supply chain from sudden cost spikes. The company says the expanded pledge will support tens of thousands of American jobs across its own workforce and supplier network. Wall Street, for its part, applauded the direction: Apple shares climbed after the announcement as investors bet the policy trade‑offs look more favorable for a company seen as strategically important to the U.S. tech base.

Yet for all the patriotic rhetoric, Apple is not promising an all‑American iPhone. Final assembly of the flagship device will remain overseas for now, the company and officials have made clear. The more immediate priority is to anchor higher‑value activities in the U.S.: silicon design and packaging, certain radio‑frequency components, precision glass, lasers and sensors, and the wafer and tooling ecosystem that underpins advanced chipmaking. Those moves could, over time, increase the domestic content of Apple hardware even if the last mile of assembly continues to happen in Asia.

So what exactly is inside the $600 billion? Based on disclosures and reporting, the tally spans four rough buckets:

•Manufacturing and suppliers. Long‑term contracts and co‑investment intended to expand domestic production of wafers, RF modules, optical components and battery materials; purchase commitments that help finance new lines at U.S. plants; and tooling or grants earmarked for specific fabs in states like Texas, Arizona and New York.

•Semiconductor ecosystem. Spending tied to U.S. chip design, testing and advanced packaging — including partnerships with foundries and equipment makers — meant to reduce reliance on Asian hubs.

•Capex beyond factories. New and expanded data centers and AI infrastructure that support Apple services but do not directly add manufacturing capacity.

•R&D and content. U.S. research outlays and domestic production of Apple TV+ shows and films that Apple has historically counted toward its U.S. economic impact.

Parsing those categories reveals why comparisons to prior promises can mislead. In February, Apple said it would spend more than $500 billion in the U.S. over four years. The August top‑up to $600 billion appears to be a blend of new supplier commitments and previously planned expenditures that now qualify under the broadened initiative. Without standardized definitions, third‑party estimates risk either double‑counting supplier capex that Apple’s contracts support or, conversely, omitting meaningful procurement that enables new domestic capacity to exist at all.

The geographic footprint is coming into focus. Texas has emerged as a headline winner, knitting together a cluster that includes GlobalWafers in Sherman, TI fabrication nearby, and activity around Austin tied to Applied Materials and Samsung. Elsewhere, Apple has flagged work with partners such as Broadcom for U.S.‑made radio components and with TSMC on chips destined for Apple Silicon — part of a national push that spans Arizona, upstate New York and the Mountain West. States are layering their own incentives atop federal subsidies to compete for each tranche of equipment and jobs.

Investors will want to track three needles. First, the domestic‑content share in Apple’s flagship devices: do U.S.‑made wafers, RF modules and glass translate into a measurable uptick in the bill of materials over the next iPhone cycles? Second, the cadence of supplier ramp‑ups: wafer yields, tool deliveries and workforce pipelines are real bottlenecks. Third, the tariff environment: if exemptions hinge on documented U.S. investment, Apple’s reporting will be scrutinized more closely by both regulators and rivals.

Skeptics warn that big‑number announcements can obscure the operational realities of industrial policy: construction delays, shortages of skilled technicians, and the difficulty of stitching together a supply chain that Asia spent decades perfecting. Supporters counter that Apple’s scale — and its ability to de‑risk supplier projects with offtake agreements — is exactly what Washington is trying to mobilize. Both can be true. A $600 billion headline does not guarantee on‑shoring overnight, but it does signal that the gravitational pull of Apple’s spending is shifting closer to home.

Bottom line: Apple’s pledge is a consequential vote of confidence in the idea of ‘Made in America,’ and it will almost certainly accelerate domestic capacity for critical components. It is also a composite metric that mixes true factory investment with broader spending that keeps Apple’s ecosystem humming. Until the company publishes clearer, auditable categories — and suppliers break out how much of their capex is directly financed by Apple — the real scale of the manufacturing push will remain hard to measure.

Notes: This article is based on contemporaneous reporting and Apple’s public statements as of Aug. 8, 2025.