Record prices, thin supply, and a new appetite for conversions are reshaping the Czech capital’s housing market

For would-be buyers in Prague, the numbers no longer whisper—they shout. The average advertised price for a new-build apartment surpassed CZK 170,000 per square meter this summer, a symbolic threshold that would have seemed fanciful only a few years ago. Yet apartments continue to sell. Developers report 4,300 new flats sold in the first half of 2025—up 23 percent year on year—despite higher price tags. In a market long defined by scarcity, demand still has the upper hand.

That imbalance is especially visible in the thin pipeline of new homes. At the end of June, roughly 5,750 new apartments were available for sale in Prague—barely two years’ worth of today’s sales—and the figure has hovered around the 5,500–5,700 range for months. Nationally, the number of completed dwellings fell to just over 30,000 in 2024, down more than a fifth from the previous year. The supply shock of the pandemic and energy crisis has eased, but construction capacity, permitting delays, and financing constraints continue to choke the flow of new housing in the capital.

Affordability metrics underscore the stress. According to Deloitte’s 2025 Property Index, Prague ranks among the least affordable cities in Europe. A typical 70‑square‑meter new apartment costs nearly CZK 12 million—roughly 15 average annual salaries. Wages are rising, but not nearly fast enough to catch housing costs, and renters are feeling the squeeze as well. In Prague, average rents for a 70‑square‑meter unit now exceed CZK 28,000 per month in many neighborhoods.

A market that sells—even at record highs

Developers say today’s buyers are a mix: households that delayed purchases during the rate spike of 2022–2023, first‑time buyers racing against further price increases, and investors returning to exploit rental demand. The steady normalization of mortgage lending has helped, even if rates remain higher than pre‑pandemic levels. Crucially, buyers have adapted. Smaller, more efficient layouts dominate sales, and proximity to transit commands a premium. Along Prague’s metro network, average asking prices now exceed CZK 7 million for a 70‑square‑meter flat at every station; the most coveted locations well surpass that.

Supply is responding—but slowly. Big, long‑gestation masterplans (from Smíchov to Rohan City) are inching forward, yet few will add meaningful numbers of keys in the next year. That’s why a growing share of new homes is coming from an old‑world tool that is suddenly fashionable again: adaptive reuse.

Conversions: an old idea finds new urgency

Converting non‑residential buildings into housing is common in Western Europe and the United States. In Czechia, it has been slower to catch on. That is changing. Rising construction costs, stricter energy standards, and the limited pipeline of new projects are pushing owners to re‑imagine older assets—especially secondary office buildings and tired hotels—whose best days as commercial properties are behind them.

Consultancies estimate that almost half of Prague’s office stock is functionally outdated or energy‑inefficient by modern standards. At the same time, the city’s office vacancy rate has tightened to around 6.6 percent as prime tenants cluster in newer buildings, deepening the divide between “have‑to‑fix” assets and those ready for the post‑pandemic workplace. For many landlords on the wrong side of that line, residential conversion has become a serious Plan B.

The projects are no longer theoretical. In July, the owners of Dům Radost—the landmark functionalist tower in Žižkov—secured a building permit for a wholesale makeover that will deliver more than 600 compact rental units, with an emphasis on student and starter housing, alongside cultural spaces and retail. A few blocks away, the former three‑star Hotel Vítkov has been reworked into Youston, a co‑living concept with 100‑plus micro‑apartments and extensive shared amenities.

Elsewhere in the city, the Finnish developer YIT has bought the 1990s‑era Kuta (now YIT Office) Centrum in Prague 4 with an eye to converting the complex to residential in the longer term. Investment firm Fidurock acquired an office block at Dykova 3 in Vinohrady and says it intends to turn it into housing, expanding the gross floor area in the process. The Cimex group is advancing two office‑to‑residential projects—M‑House near Kubánské náměstí and “mo‑cha home” in Pankrác—adding for‑sale and rental units respectively. Together, these schemes hint at a pipeline that, while modest in absolute terms, is far more active than Prague has seen before.

Why conversions work—and why they’re hard

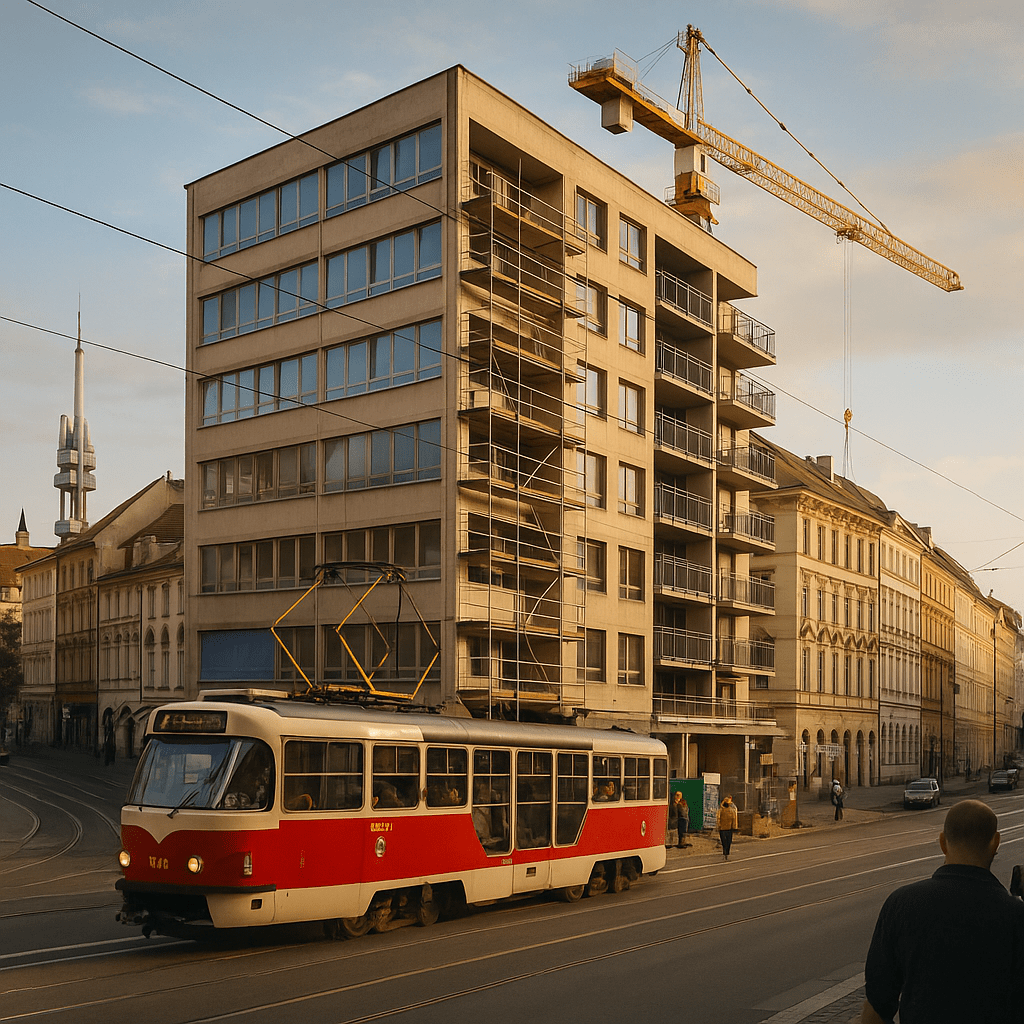

The appeal is straightforward. Conversions can bring homes to market faster than ground‑up builds because the structure, foundations, and often the core already exist. They also land housing where it’s most needed: deep inside the city, near tram lines and metro stops, with shops and schools close by. For tenants and buyers, that translates into shorter commutes and lower transport costs. For the city, it means denser, more sustainable neighborhoods with fewer greenfield pressures.

But adaptive reuse is not a cheat code. Success depends on a building’s geometry and technical baseline: floorplate depth and column spacing, daylighting, window operability, elevator and stair egress, acoustic separation, ceiling heights, and the ability to thread new plumbing stacks and ventilation shafts. Fire codes and heritage protections add layers of complexity; so do the economics. Acquisition costs, construction budgets, and exit values must align, and lenders must be comfortable underwriting unconventional collateral. Even so, the calculus looks better than it did two years ago as sellers reset price expectations for underperforming office assets while residential prices reach new highs.

What it means for buyers and renters

In the near term, conversions won’t flood the market with cheap housing. Most projects target small and mid‑sized units, either for rent or for sale at the prevailing market rate. Still, the incremental additions matter. In a city that has struggled for years to add homes at scale, every building that turns the lights back on for residents relieves a bit of pressure. Expect more micro‑units and one‑bedrooms around transit hubs, and more “hybrid” buildings that mix housing with coworking, leisure, and ground‑floor services.

For buyers, the message is to be flexible on product type and open to non‑traditional layouts in older shells that have been smartly re‑engineered. For renters, new stock aimed at single professionals and students should expand options over the next 12–24 months, even as asking rents remain elevated. Investors, meanwhile, are watching energy performance certificates (EPCs) closely: renovated units with strong EPC ratings are already achieving pricing premiums and faster lease‑up.

What would help

City Hall cannot build its way out of a housing deficit overnight, but it can tilt the playing field. Three levers would make a difference now:

•Streamline permits and change‑of‑use approvals. Long decision cycles are holding back both ground‑up projects and conversions. Faster, predictable timelines would unlock marginal schemes that are currently uneconomic.

•Targeted incentives for adaptive reuse. Temporary fee reductions, density bonuses, or tax relief for office‑to‑residential projects that meet energy and affordability targets would nudge more owners off the fence. International experience—especially from North American cities now seeing record conversion pipelines—suggests these carrots can mobilize private capital quickly.

•Municipal participation. The city’s own housing stock has barely budged in years. Partnering with private owners of obsolete assets (through PPPs or long‑term leases) could deliver affordable and student housing faster than assembling new sites from scratch.

None of these measures will reverse the price curve on their own. But together with the private sector’s newfound creativity, they can change the trajectory of Prague’s housing market from chronic undersupply to steady, sustainable growth. For a generation priced out of the city they call home, that shift cannot come soon enough.

—

Sources: Developers’ H1 2025 sales and average price per m² (Trigema/Central Group/Skanska market analysis, July 30, 2025); available new‑build supply in Prague (~5,750 units as of end‑June 2025); Deloitte Property Index 2025 (Prague affordability at ~15 annual salaries; average 70 m² price ~CZK 11.94m); CZSO housing completions in 2024 (~30,274 units); Prague office vacancy (~6.6% in Q2 2025) and outdated stock share; conversion examples (Dům Radost, Youston/Hotel Vítkov, YIT Office Centrum/Kuta, Fidurock Dykova 3, Cimex M‑House & mo‑cha home).