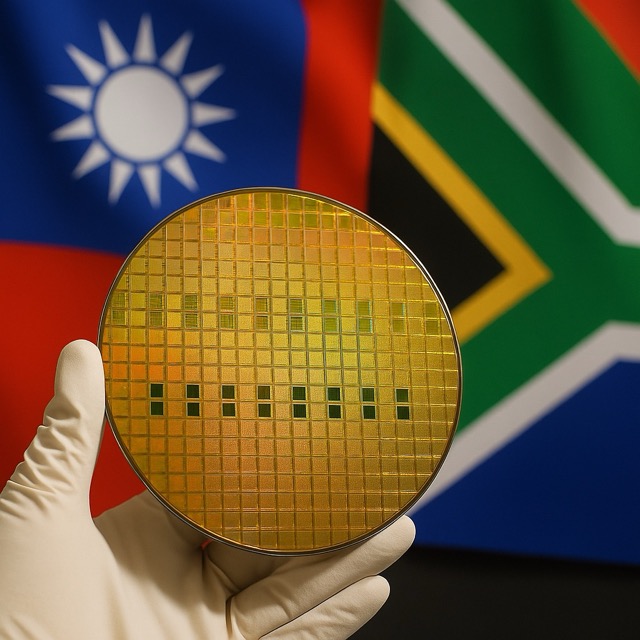

A two‑day experiment in ‘silicon statecraft’ reveals both the power—and limits—of using semiconductors as a geopolitical weapon

TAIPEI/JOHANNESBURG — Taiwan has suspended planned export controls on semiconductors bound for South Africa, halting an unprecedented foray into what analysts have dubbed ‘silicon statecraft’ just two days after announcing the measures. The freeze followed signals from Pretoria that it would enter talks with Taipei over the status of Taiwan’s representative office, according to statements from Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) and Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA).

The on‑off controls—first unveiled on Tuesday and paused on Thursday—would have shifted scores of chip categories to an approval‑only regime for South African buyers. While South Africa is not a major direct importer of Taiwan’s most advanced processors, it relies on a steady flow of Taiwanese integrated circuits, memory, and power management semiconductors used in telecommunications equipment, automotive components, and industrial systems. Even a short‑lived chill threatened to roil local supply chains and raised the specter of ripple effects across regional assemblers that source through South African distributors.

For Taipei, the gambit was an unmistakable shot across the bow: a message to countries that recalibrating ties with Taiwan under pressure from Beijing can carry consequences. Pretoria has over recent years aligned more explicitly with China’s interpretation of the one‑China principle; the latest flashpoint involves South Africa’s push to relocate Taiwan’s liaison office from the political capital, Pretoria, to Johannesburg—a symbolic downgrade that Taipei views as eroding its de facto diplomatic standing.

Officials in Taipei framed the move as a narrow, reversible instrument targeted at a single country’s actions that ‘undermine national and public security.’ Yet the swiftness of the U‑turn underscored the delicacy of weaponizing a strategically vital export. Taiwan’s semiconductor ecosystem—anchored by TSMC and a constellation of specialty foundries and component makers—touches nearly every advanced electronics supply chain. By pressing on that nerve, even lightly, Taipei risked opening itself to accusations of politicizing technology trade in ways it has long criticized Beijing for doing.

South Africa’s government, for its part, signaled that it was prepared to ‘engage in consultations’ with Taiwan. People familiar with the discussions said Pretoria sought to lower the temperature quickly, wary that a prolonged standoff could complicate domestic industrial policy goals and investment plans tied to automotive electrification, telecom upgrades, and data‑center expansion—all sectors where Taiwanese components are staples.

Diplomats and industry executives said the episode will be remembered less for its immediate economic impact than for the precedent it sets. Taiwan has traditionally cast itself as a trusted, rules‑abiding supplier in a fractious tech world. The brief experiment in punitive controls suggests that calculus is evolving as geopolitical risks mount—from China’s military pressure to tightening U.S. export regimes that increasingly shape how Taiwanese firms operate abroad, including at facilities in mainland China.

‘This was a test balloon,’ said a senior executive at a multinational electronics company with sourcing operations in both East Asia and southern Africa. ‘If diplomatic red lines are crossed, access to certain chips can become uncertain. That is a powerful signal even if the controls never took effect.’

The policy move also sparked a broader debate within Taiwan’s government and industry over the right balance between foreign‑policy signaling and economic self‑interest. Some lawmakers close to President Lai Ching‑te have urged a tougher posture, arguing that Taiwan’s chip dominance is one of the few coercive levers it has short of military means. Others warn that making semiconductors an overt diplomatic cudgel could erode customer trust and invite retaliatory measures or regulatory scrutiny in key markets.

In practical terms, the halted order would have required export pre‑approval for 47 product categories, according to people briefed on the draft notice. These included various types of integrated circuits and memory, wafers, and selected power and radio‑frequency components. Officials described the measure as temporary and targeted, with license reviews focusing on end‑use assurances and supply‑chain transparency.

Economists say the wider market shock was contained by the rapid pause. South Africa’s domestic semiconductor design activity is limited, and its import demand skews toward mature nodes used in automotive, energy, and infrastructure. But the chill reverberated through regional logistics networks and among global OEMs that depend on South African assembly or after‑market channels. ‘Even the hint of licensing delays can trigger precautionary buying and re‑routing,’ said a components distributor based in Dubai. ‘Nobody wants to be caught short in Q4 production runs.’

Beyond the bilateral spat, the affair unfolds against a global clampdown on technology flows. Washington this month tightened export rules affecting chipmaking tools in Chinese fabs, a step that also hits Taiwanese champions operating in the mainland. Taipei has expanded its own entity lists and compliance framework, adding prominent Chinese tech firms and emphasizing end‑use controls. The South Africa move—though paused—was the first time Taipei applied a unilateral country‑specific semiconductor lever to advance a diplomatic objective.

Whether the tool returns will depend on how talks proceed, officials say. If Pretoria agrees to preserve meaningful access and visibility for Taiwan’s representative presence, the controls could be shelved indefinitely. If talks stall—or if additional steps are taken that Taipei reads as downgrades—the licensing regime could be revived on short notice. A person familiar with the government’s thinking likened it to a ‘loaded but holstered’ policy.

The dust‑up also highlighted Africa’s growing relevance in the semiconductor value chain. Although the continent manufactures few chips, its markets are pivotal for downstream electronics, telecom equipment, and automotive assembly. Countries like South Africa are courting data‑center investment and EV supply chains, which depend on reliable access to everything from power‑management ICs to networking silicon. Disruptions—actual or feared—can ripple outward to partners in Europe and the Middle East that stitch together regional distribution and service networks.

Investors took the episode as a reminder that geopolitics can move faster than capacity plans. Shares of major chipmakers were largely unmoved, according to traders, but procurement teams quietly dusted off contingency plans. Several multinational manufacturers said they would review dual‑sourcing options and buffer inventories for South African operations through the first quarter of 2026, in case the policy pendulum swings back.

For now, both sides appear to have achieved tactical aims: Taipei demonstrated it can reach for the semiconductor lever if pushed, while Pretoria avoided immediate disruption and opened a channel for de‑escalation. The larger strategic question—can small, open economies wield industrial chokepoints without undermining their own reputation as dependable suppliers—remains unsettled.

As talks get underway, companies will watch two timelines. The first is political: any movement on the location and status of Taiwan’s liaison office in South Africa. The second is regulatory: whether Taiwan publishes a revised control list or guidance clarifying how and when approval‑based regimes might be triggered in the future. Each will determine whether this week’s pause reads as a one‑off misfire—or the opening chapter of a new era in semiconductor diplomacy.

Sourcing & context: Public statements from Taiwan’s MOEA and MOFA and reporting by multiple international and regional outlets between September 24–27, 2025 indicate the curbs were announced Tuesday and suspended Thursday following South Africa’s willingness to hold talks. Analysts characterize the move as an unprecedented use of Taiwan’s semiconductor leverage in a country‑specific diplomatic dispute.

References:

• Bloomberg (Sept. 25, 2025): Taiwan suspends South Africa chip export curbs after two days.

• Financial Times (Sept. 26, 2025): Taiwan backtracks on chip export curbs to South Africa after China spat.

• Taipei Times (Sept. 25–26, 2025): MOEA halts South Africa chip export curbs; Taiwan weaponizes chip sector to deter Beijing.

• Focus Taiwan (Sept. 25, 2025): Taiwan suspends tech export rules after S. Africa agrees to talk.

• African Business (Sept. 26, 2025): Taiwan u‑turns on chip export controls to South Africa.