A September 2025 look at how the sudden liquidation of Tricolor ripples through borrowers, banks and bond markets—even as headline indicators say the U.S. economy is still holding up.

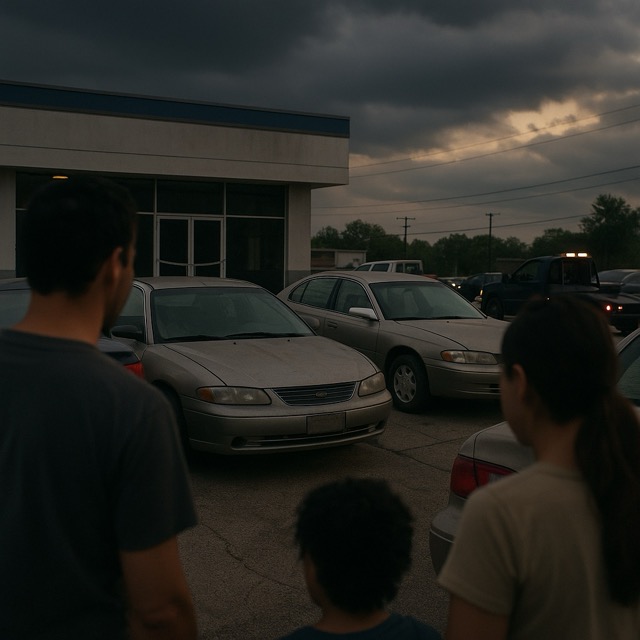

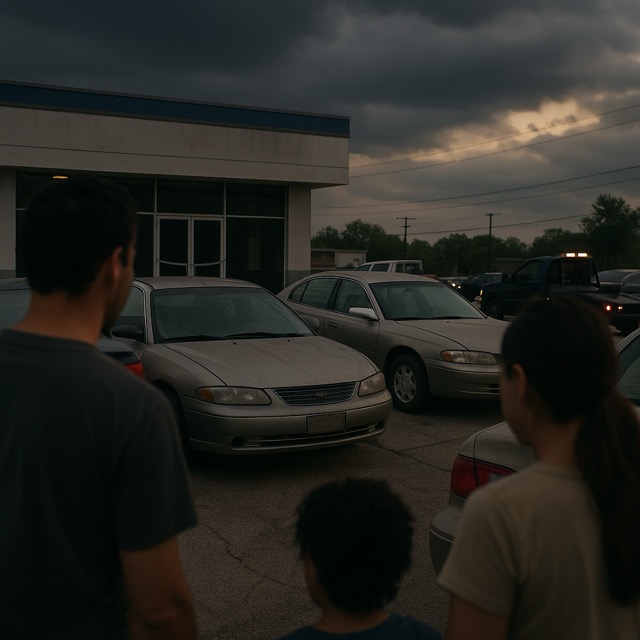

DALLAS — Tricolor Holdings, a prominent buy-here-pay-here used‑car chain and subprime auto lender that catered largely to Spanish‑speaking and thin‑file borrowers across the Southwest, collapsed into Chapter 7 liquidation earlier this month. The implosion was abrupt: stores shuttered, employees found themselves locked out, and a court‑appointed trustee began sorting out who controls roughly 100,000 active car loans. Federal and state probes have been opened, according to people familiar with the matter and public reports, and banks are assessing potential losses.

The company’s straight‑to‑liquidation filing is unusual for a business of its size. It has also become a stress test for an uneasy corner of consumer finance that flourished during years of easy money: subprime auto. In that market, dealer‑lenders extend credit to borrowers with limited credit histories, then finance those receivables with warehouse lines or sell them into asset‑backed securities (ABS). When a dealer‑lender fails, borrowers can be stranded—unsure where to send payments or whether a repossession looms—and servicers must be swapped in quickly to prevent cascading losses.

On the ground, confusion is widespread. In Houston and across Texas, customers interviewed by local stations described missed title transfers, unreturned trade‑ins and unanswered phone lines. Consumer advocates warn that even paperwork hiccups can be devastating for precarious households: a missed title can translate into registration problems or fines; a late payment can drop a credit score and raise the cost of future borrowing. The risk is highest for borrowers who live paycheck to paycheck and cannot easily absorb a surprise bill or a temporary payment disruption.

For now, the immediate instruction to borrowers is simple and counterintuitive: keep paying. Even though Tricolor’s sales operations have shut down, many of its loans were owned by securitization trusts or banks, not by the dealership itself. Missing payments risks late fees, credit damage and repossession regardless of the dealer’s fate. The bankruptcy trustee is moving to designate a long‑term servicer so that accounts can be boarded and billing normalized. Until that happens, borrowers are being told to follow their most recent lender instructions and maintain records of every payment.

Behind the scenes, the collapse has rippled through credit desks. Bankers and investors who bought Tricolor’s securitized bonds—some of which carried strong ratings—are re‑examining collateral files and representation warranties. Warehouse lenders exposed to the company have tightened advance rates for similar lenders and are combing through covenants across portfolios. The timing was unfortunate: the Tricolor debacle arrived just as First Brands Group, a large auto‑parts supplier that relied on invoice‑backed financing, revealed severe funding stress of its own. Together, the cases have rekindled a broader debate about how much risk has migrated from banks to private credit and securitization vehicles over the past decade.

The macro backdrop, meanwhile, looks deceptively calm. The U.S. unemployment rate held at 4.3% in August, essentially unchanged over the year, and payrolls continued to expand modestly. Inflation has cooled from its 2022 highs: headline consumer prices rose 2.9% year over year in August, though monthly gains picked up on shelter and used cars. Those aggregates suggest an economy that is slowing but still resilient.

Yet the experience of low‑income households—who are most likely to take out subprime auto loans—has diverged from the averages. Delinquencies across credit products have crept higher: TransUnion reports consumers 60‑plus days past due reached 1.31% in the second quarter, exceeding the rate seen in 2009. In auto finance specifically, lenders cite a painful mix of elevated vehicle prices, expensive insurance and out‑of‑pocket repairs. In many cities, eviction filings are running above pre‑pandemic baselines, a sign that housing burdens remain intense even as inflation cools. These pressures compound for families whose budgets hinge on reliable transportation to get to work and childcare.

Subprime auto sits at the intersection of those strains. Used‑car prices remain materially higher than in 2019, and while dealer margins have normalized, average monthly payments for both new and used vehicles remain near records. For borrowers with limited credit histories, higher interest rates and add‑ons can push payment‑to‑income ratios into precarious territory. Income volatility—common in hourly or gig work—widens the gap between due dates and cash flow. One medical bill or a week of missed shifts can turn a manageable payment into a delinquency, and a delinquency can quickly become a repossession.

This is why Tricolor’s failure matters beyond one company’s alleged missteps. If collateral was overstated or loans were churned too aggressively, the clean‑up could tighten credit for the very borrowers who have few alternatives. Banks and ABS investors are already revisiting underwriting guardrails put in place over the last two years, including higher minimum FICO thresholds, lower loan‑to‑value caps and closer verification of income and employment. Warehouse lenders have begun to require more granular reporting on early‑payment defaults and charge‑offs. These moves improve loan quality, but they also mean fewer approvals and higher APRs at the margin.

Still, the broader market is not flashing red. Investor demand for securitized products persists, and programmatic issuers continue to print deals—albeit at wider spreads and with tougher structures. Trade groups argue that Tricolor looks idiosyncratic, not systemic. Even so, idiosyncratic shocks can be meaningful if they disproportionately hit communities with few transit alternatives. For many lower‑income households, a used car is not a discretionary purchase; it is the link to employment. Losing that link because a lender failed—or because a temporary servicing mess triggered a missed payment—can have cascading effects on earnings and housing stability.

What to watch next: First, the trustee’s choice of a long‑term servicer and any friction as accounts are transferred. Second, whether warehouse lenders or ABS investors file repurchase claims if they find inaccurate collateral representations. Third, the trajectory of 60‑day auto delinquencies through the winter, historically the peak season for repossessions. And finally, any spillovers from other corners of asset‑backed finance—such as invoice‑backed funding—where originators’ controls come under scrutiny.

If the macro economy continues on a slow‑and‑steady path—moderate inflation, an unemployment rate in the low‑4s—these micro‑level stressors may register not as a full‑blown crisis but as a drag: fewer approvals for borderline borrowers, slightly higher APRs, and more frequent repossessions in already stressed ZIP codes. That would still feel like a downturn to the households living it. The policy challenge is to improve access to reliable transportation without recreating the incentives that encouraged sloppy underwriting. That may mean targeted support for credit‑building products, stricter policing of payment packing and add‑ons, and investments in transit for places where driving is the only option today.

The story of Tricolor is still being written in bankruptcy court. For the borrowers whose commutes depend on cars financed through its lots, the more pressing story is whether they can get to work on Monday—and whether the next payment keeps the tow truck away.

Sources

• WSJ: “Collapse of Subprime Lender Tricolor Kicks Off Scramble for 100,000 Car Loans” (Sept. 18, 2025).

• Bloomberg Law: “Tricolor Downfall Is Rare Straight‑to‑Chapter 7 for Big Business” (Sept. 24, 2025).

• Bloomberg News: “Tricolor’s New Loan‑Service Team Is Locked Out of the Building” (Sept. 26, 2025).

• AutoRemarketing: “Fallout from Tricolor bankruptcy intensifies throughout subprime space” (Sept. 15, 2025).

• Kelley Blue Book: “A Big Auto Lender Went Bankrupt. Here’s What It Means.” (Sept. 12, 2025).

• BLS: The Employment Situation — August 2025 (released Sept. 5, 2025).

• BLS: Consumer Price Index — August 2025 (released Sept. 11, 2025).

• TransUnion: Q2 2025 Credit Industry Insights — auto 60+ DPD at 1.31%.

• Princeton Eviction Lab: Eviction Tracking System (updated Sept. 1, 2025).

• Reuters/FT coverage of First Brands Group funding stress and affiliate bankruptcies (Sept. 25–27, 2025).