A rare emergency move under the Goods Availability Act puts a Dutch-based semiconductor maker under state direction to keep production and know‑how in Europe.

The Netherlands has taken direct control of Nexperia, a Dutch-headquartered semiconductor manufacturer owned by China’s Wingtech Technology, in an extraordinary step to ensure essential chip supplies remain available to Europe. Announced on October 12–13, 2025, the intervention—taken under the country’s Goods Availability Act (Wet beschikbaarheid goederen)—gives the Minister of Economic Affairs temporary powers to block or reverse corporate decisions deemed harmful to national or European economic security. Routine production continues, but governance at the company has been restructured and certain senior executives linked to the Chinese parent have been suspended, pending independent oversight, according to government notices and company statements.

Officials framed the decision as a supply‑security measure rather than an outright expropriation. The order restricts asset transfers, changes to leadership, or moves that could relocate key operations outside the European Union without state approval for a defined period—initially up to one year. The Ministry of Economic Affairs said the aim is to prevent a scenario in which chips or semi‑finished goods “would become unavailable in an emergency,” while stabilizing governance at a company considered vital to Europe’s industrial base.

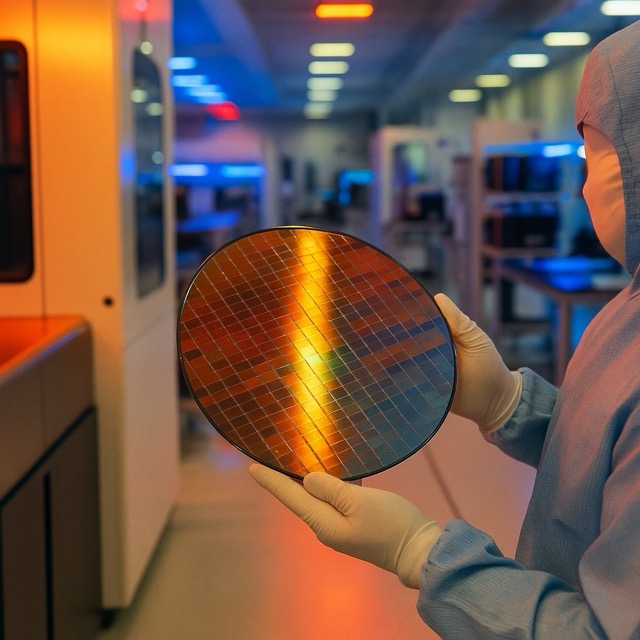

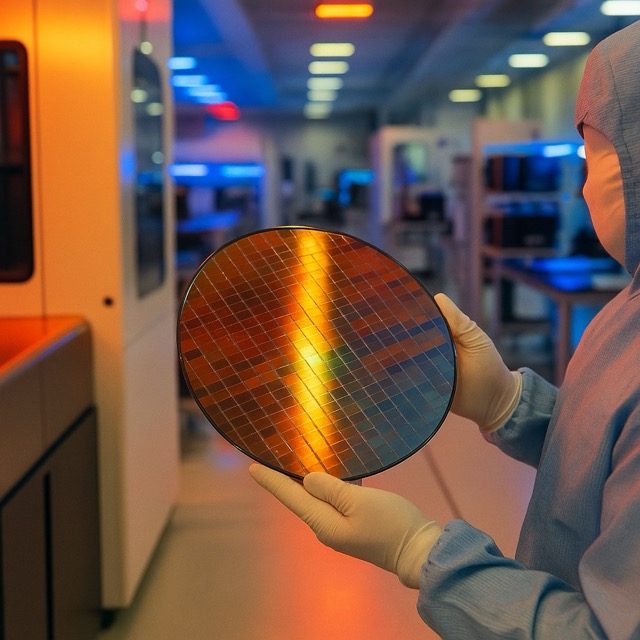

Nexperia, headquartered in Nijmegen, produces a high volume of power management and discrete components that quietly underpin automotive electronics, industrial systems, smartphones, and an array of consumer devices. While far from the bleeding edge of logic processors, these parts are the bedrock of modern manufacturing: a shortage of small signal diodes or MOSFETs can idle an auto line as effectively as the absence of an advanced processor. Europe’s post‑pandemic experience with supply snarls—and the bruising lessons from the 2021–22 chip crunch—made continuity of these components a strategic concern.

The move lands at the intersection of two powerful currents: Europe’s push for “strategic autonomy” in critical technologies, and the broader geopolitical decoupling pressures surrounding Chinese investment in Western tech supply chains. Wingtech acquired Nexperia in 2018, part of a wave of outbound Chinese deals. Since then, scrutiny of Chinese ownership in sensitive sectors has steadily tightened, including in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and the United States. Nexperia’s ill‑fated acquisition of the Newport Wafer Fab in Wales—ultimately blocked by the UK government in 2022 on national security grounds—became an early flashpoint.

Market reaction was swift. Shares of Wingtech fell sharply in Shanghai trading after the Dutch announcement as investors braced for a prolonged period of constrained control over the European subsidiary. Nexperia said it complies with export and sanctions rules and emphasized that manufacturing will continue to support customers. But the company offered little detail on how decision‑making will work day‑to‑day under state supervision—particularly on capital expenditure, product roadmaps, and customer prioritization if supply tightens.

For The Hague, the measure tests the scope of its emergency economic toolkit. The Goods Availability Act is designed for exceptional situations that threaten the availability of critical goods. Officials have been at pains to cast the step as “targeted and temporary,” tethered to specific governance failures and supply‑risk indicators, not a blanket policy towards any particular country. Nevertheless, Beijing condemned the intervention as discriminatory and politically motivated, signaling that a diplomatic dispute is likely to follow.

The Netherlands’ gambit also dovetails with the European Union’s broader ambitions under the EU Chips Act to rebuild manufacturing, strengthen R&D, and secure supply chains. While headline‑grabbing investments focus on advanced logic and foundry capacity, the less glamorous world of power discretes and analog devices is where production resilience can be won or lost. Industrial groups across the continent—especially carmakers and Tier‑1 suppliers in Germany, the Netherlands and Central Europe—have lobbied for predictable access to exactly the types of components Nexperia makes.

Analysts say the immediate impact for customers should be limited: lines are running, logistics are intact, and there is no signal of export restrictions on outgoing products. But the governance shake‑up could delay new lines or packaging transitions, and the state’s veto power over strategic decisions may introduce uncertainty for global clients and suppliers. If the guardrails extend beyond the initial period, Nexperia may need to revisit partnerships, IP-sharing arrangements, or plans to expand outside the bloc.

There is also the matter of talent and intellectual property. The order reportedly includes steps to appoint an independent, non‑Chinese director with decisive voting rights while certain decision‑making authority is held in trust—measures intended to keep technology stewardship anchored in the Netherlands. Employee morale and retention will be a key variable, particularly in a tight European labor market for seasoned power‑electronics engineers and manufacturing technicians.

For China and Europe alike, the episode underscores a world in which corporate ownership and national security are increasingly entangled. Chinese investment helped preserve and scale several European tech assets over the past decade; now, political risk is pushing host governments to assert new controls, especially where dual‑use or chokepoint technologies are involved. That raises the cost of cross‑border deals and forces multinational tech firms to build compliance and governance plans robust enough to withstand sovereign intervention.

Over the medium term, the Netherlands will face a balancing act. Too heavy a hand risks chilling investment and entangling the state in the micro‑management of a global supply node. Too light a touch risks a repeat of the vulnerabilities exposed during the pandemic-era chip shortages and the ongoing techno‑strategic rivalry between Washington and Beijing. The success of this intervention will be judged by whether Nexperia can deliver uninterrupted, competitively priced components to European manufacturers while also maintaining global customer relationships.

What happens next? Lawyers expect challenges in Dutch courts from Wingtech as well as potential WTO‑tinged rhetoric at the EU‑China level. The Dutch cabinet will assess whether to maintain, relax, or tighten the restrictions as the one‑year window progresses, based on governance milestones and supply‑risk metrics. If the framework proves workable—keeping factories humming while safeguarding know‑how—it could become a template for other European capitals confronting similar ownership dilemmas in critical sectors.

For now, Europe’s automotive and industrial ecosystems will welcome the promise of stability, even if it comes with state oversight strings attached. In a market where a missed shipment of a few‑cent components can halt multi‑million‑euro assembly lines, The Hague has decided that insurance is worth the political price.