Nine top generals have been expelled from the Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army — a move less about fighting corruption than about tightening control ahead of key political reshuffles.

When Beijing announced last week that nine of China’s highest-ranking generals — including Central Military Commission (CMC) Vice-Chairman He Weidong and senior political officer Miao Hua — had been expelled from both the Communist Party and the army, state media framed it as another victory in the Party’s “zero-tolerance fight against corruption.”

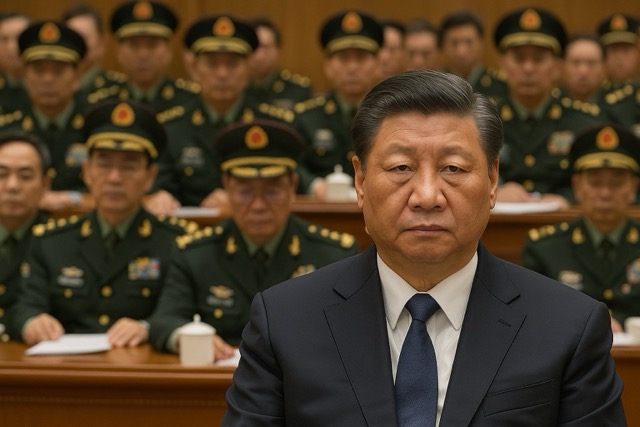

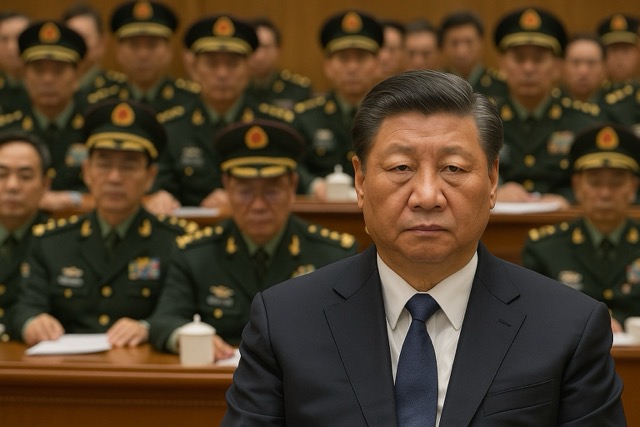

But few in Beijing or abroad believe this is only about graft. The sheer scale of the purge, the seniority of those targeted, and the timing — just months before the next Party plenary session, where military appointments are set to be reshuffled — all point to something deeper: President Xi Jinping tightening his grip on the only institution that could ever threaten his rule.

A purge disguised as moral rectitude

Officially, the nine were found guilty of “serious disciplinary and legal violations,” a phrase used so often it has become code for political disloyalty. Their cases have been handed to military prosecutors. In total, they include former commanders of the Rocket Force, the Navy, and the People’s Armed Police, as well as senior officials from the CMC’s Political Work Department — precisely the branches that control loyalty, weapons, and ideology.

Xi’s anti-corruption rhetoric, while popular among the Party faithful, increasingly resembles a tool of political hygiene: eliminating not just corruption, but uncertainty. Each purge serves as a reminder that the Party’s discipline machinery answers to Xi alone, and that personal loyalty now outweighs competence or seniority.

Consolidating power before the next reshuffle

This is not the first such sweep. Former Defense Minister Li Shangfu and Rocket Force Commander Li Yuchao both vanished from public view last year before being quietly removed. The new expulsions extend the campaign to the very top of the CMC — an institution theoretically under the Party’s control, but in practice wholly dominated by Xi, its chairman and commander-in-chief.

With next year’s plenary session approaching, Xi appears determined to rebuild the upper echelons of the military in his own image, ensuring that every key command position is held by a loyalist. As one Beijing academic put it, “This is not a clean-up — it’s a lock-down.”

Fear as a governing tool

While state media hails the move as a triumph of discipline, insiders describe an atmosphere of growing fear within the ranks. Senior officers are keeping their heads down, avoiding any appearance of ambition or independence. In a system where proximity to power can suddenly become a liability, silence has become the new loyalty.

The purge also reflects Xi’s strategic insecurity at a time when China faces mounting external pressures — from economic stagnation to tensions with the United States over Taiwan and the South China Sea. A nervous leadership, critics say, is turning inward, eliminating any possible challenge before it materializes.

The cost of control

Xi’s relentless pursuit of “purity” may consolidate his personal authority, but it comes at a price: a military increasingly governed by fear rather than professionalism. When loyalty eclipses merit, decision-making becomes brittle — and the chain of command less capable of honest feedback or initiative.

In the long run, the Party’s greatest danger may not come from corruption, but from the hollowing out of trust and morale within its own armed forces.

As one former Chinese diplomat now in exile put it: “Xi’s anti-corruption drive is no longer about cleaning up the system. It’s about cleaning out anyone who might think for themselves.”