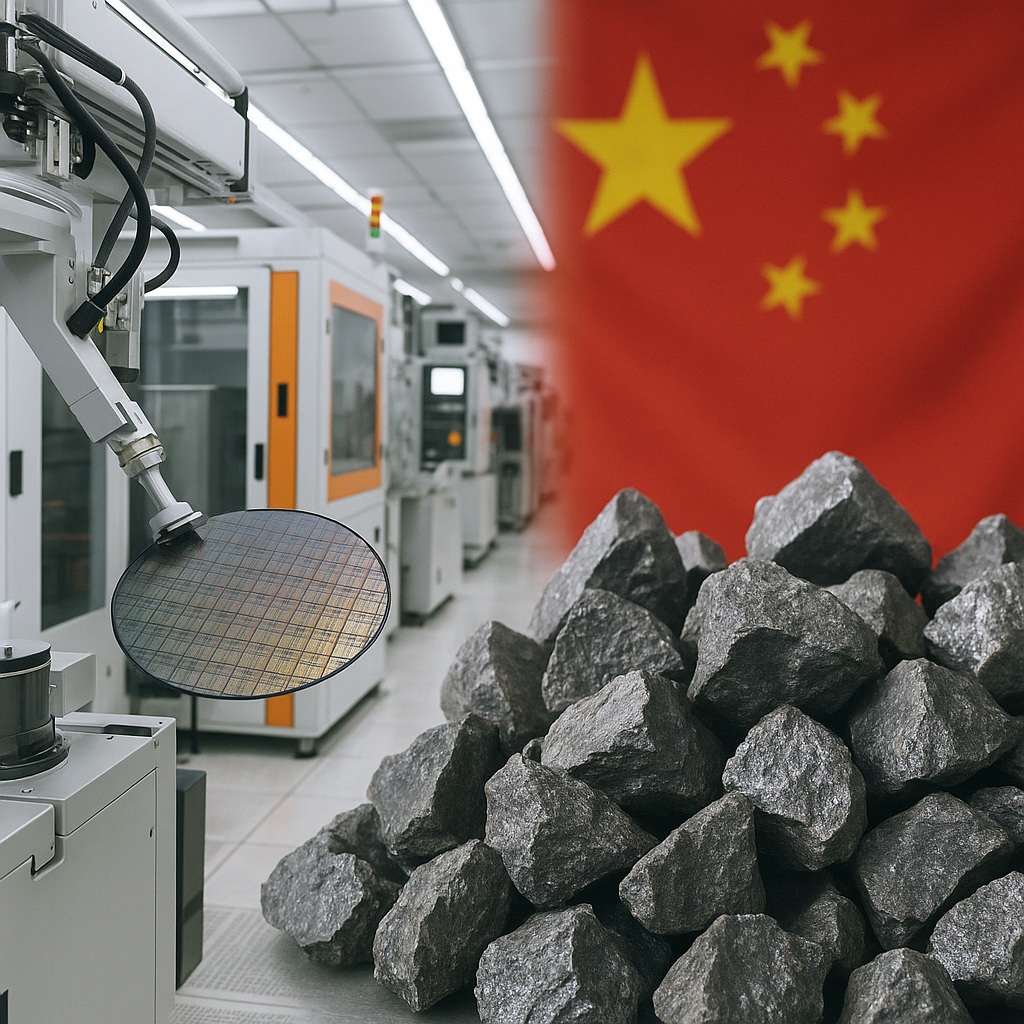

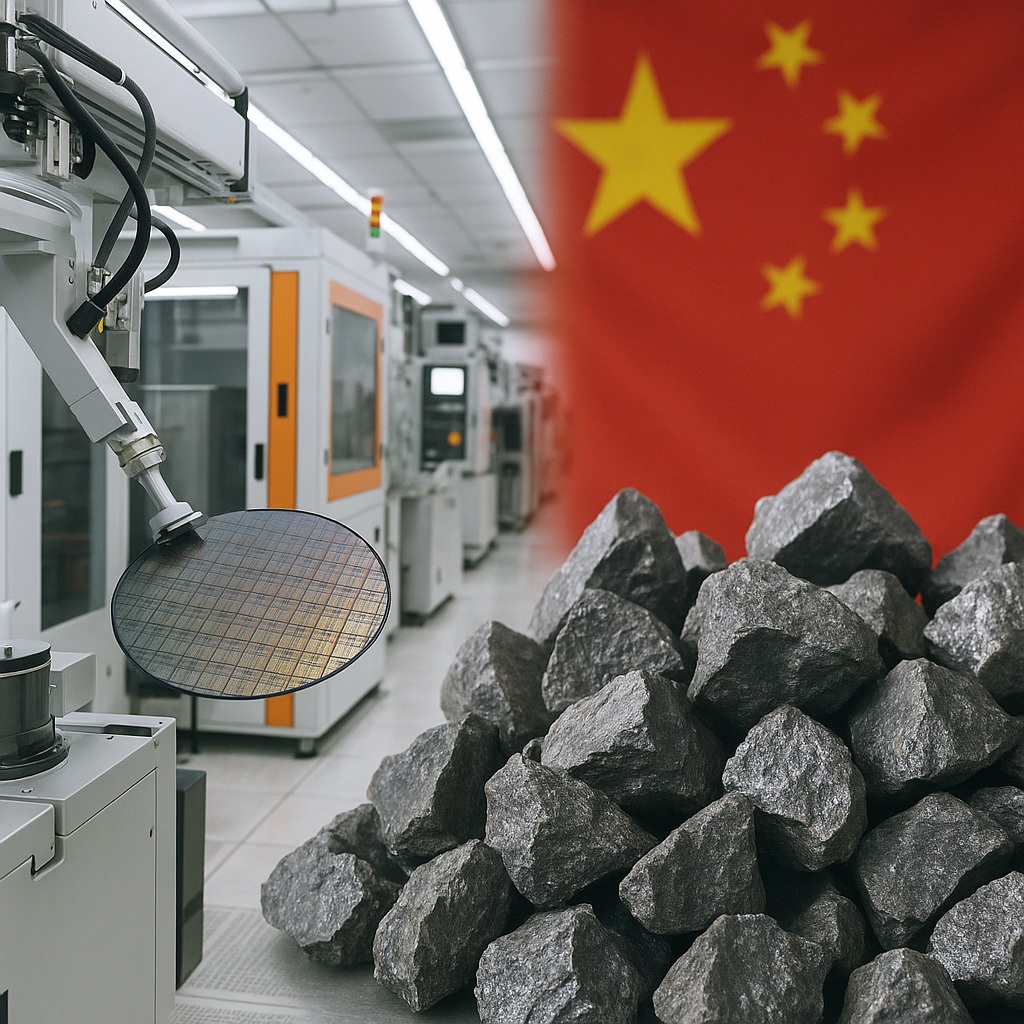

A widening confrontation over chip‑mineral supply chains reveals Beijing’s escalating use of economic pressure as geopolitical weaponry

The dispute surrounding Nexperia, the Chinese-owned semiconductor manufacturer operating widely across Europe, has become the latest flashpoint in the increasingly adversarial relationship between Beijing and the European Union. What initially appeared to be a conventional regulatory matter has evolved into a broader political struggle, in which China is leveraging its dominance over critical chip‑related mineral supply chains to exert pressure on Brussels.

Across diplomatic channels, industry forums, and boardrooms, officials now describe the conflict as a turning point. It is not merely about a single company’s compliance record or acquisition history. Instead, it illuminates how China is transforming economic interdependence into strategic advantage, using essential raw materials—particularly gallium, germanium, and rare earth elements—to signal its displeasure with Europe’s tougher stance on security-sensitive investments.

European policymakers privately acknowledge that the incident has forced a deeper reconsideration of the continent’s vulnerability. For years, the EU treated technological cooperation and supply‑chain integration with China as mutually beneficial. Now, the Nexperia row underscores the degree to which those linkages can be weaponised. Beijing’s moves have been subtle but unmistakable: slowed customs approvals for certain European-bound mineral shipments, heightened export‑licensing scrutiny, and rhetorical messaging about Europe’s “unfriendly” investment reviews.

Business leaders say these actions have produced cascading uncertainty. Several European semiconductor firms report longer lead times for inputs tied to Chinese extraction or refining operations. While no formal embargo has been declared, the implicit threat is sufficient to unsettle production planning. Analysts caution that the psychological effect—fear of abrupt disruption—can be nearly as damaging as an actual cutoff.

For Beijing, the timing is deliberate. European institutions are intensifying examination of foreign investment in critical technologies, with semiconductor assets among the most affected. Nexperia, owned by a major Chinese electronics conglomerate, has been under heightened scrutiny following concerns about national security, intellectual property control, and the integrity of supply chains. China has interpreted these measures as discriminatory and politically motivated, prompting retaliation calibrated to demonstrate its enduring leverage.

The EU’s challenge lies in walking a narrow line. Brussels aims to assert control over strategic sectors without provoking outright confrontation or sparking damaging supply shocks. Officials recognise that Europe is still years away from reducing structural dependence on Chinese mineral processing, despite efforts to diversify partners and establish domestic refining capacity. The current impasse illustrates the gap between policy ambition and industrial reality.

Industry specialists warn that the Nexperia dispute could accelerate a gradual decoupling dynamic. Several European member states have already taken steps to restrict Chinese acquisitions in high‑technology fields. Others are revisiting earlier approvals, drawing criticism from Beijing and concern from multinational investors. The result is an environment marked by mutual suspicion and constrained negotiation space.

The semiconductor sector sits at the centre of this standoff. Chips underpin every major industrial and digital transformation project on the continent, from electric mobility to advanced manufacturing and telecommunications. Yet the materials required for chip fabrication remain concentrated in a handful of geographies—China foremost among them. That concentration gives Beijing an instrument of influence that Europe, for now, cannot counterbalance.

In interviews, EU officials involved in trade and industrial strategy describe growing apprehension. While none expect an immediate collapse of relations, they concede that the trajectory is negative. Europe’s attempt to navigate between security imperatives and commercial pragmatism is increasingly strained. China, for its part, appears determined to demonstrate that Europe’s choices carry consequences.

The longer the dispute continues, the more likely it will reshape strategic planning within both regions. European firms may accelerate efforts to secure non‑Chinese mineral supply, even at higher cost. China may further entrench its policy of using export controls as geopolitical signalling. And both sides may find that the interdependencies once regarded as stabilising elements are, in practice, sources of tension.

For now, the Nexperia case serves as a vivid illustration of a new era in China–EU relations. Economic ties remain extensive, but they no longer provide insulation against political friction. As Europe tightens oversight of critical infrastructure and technology, Beijing is demonstrating a willingness—and an ability—to apply pressure through the chokepoints it dominates.

The implications extend far beyond one company. They cut to the heart of the global contest for technological primacy and the raw materials that enable it. Europe’s response in the coming months will reveal whether it can defend its regulatory autonomy without succumbing to supply‑chain coercion, or whether China’s leverage will compel a recalibration of the EU’s approach to its most significant trading partner.

What is clear is that the Nexperia dispute is no longer simply a corporate or regulatory matter. It is a strategic confrontation shaped by competing visions of technological sovereignty, national security, and economic resilience. And it marks a decisive moment in the evolution of China’s willingness to deploy its mineral might as a geopolitical tool.