An EU warning casts China’s trade diplomacy as a strategic instrument, highlighting a year-end shift in global politics.

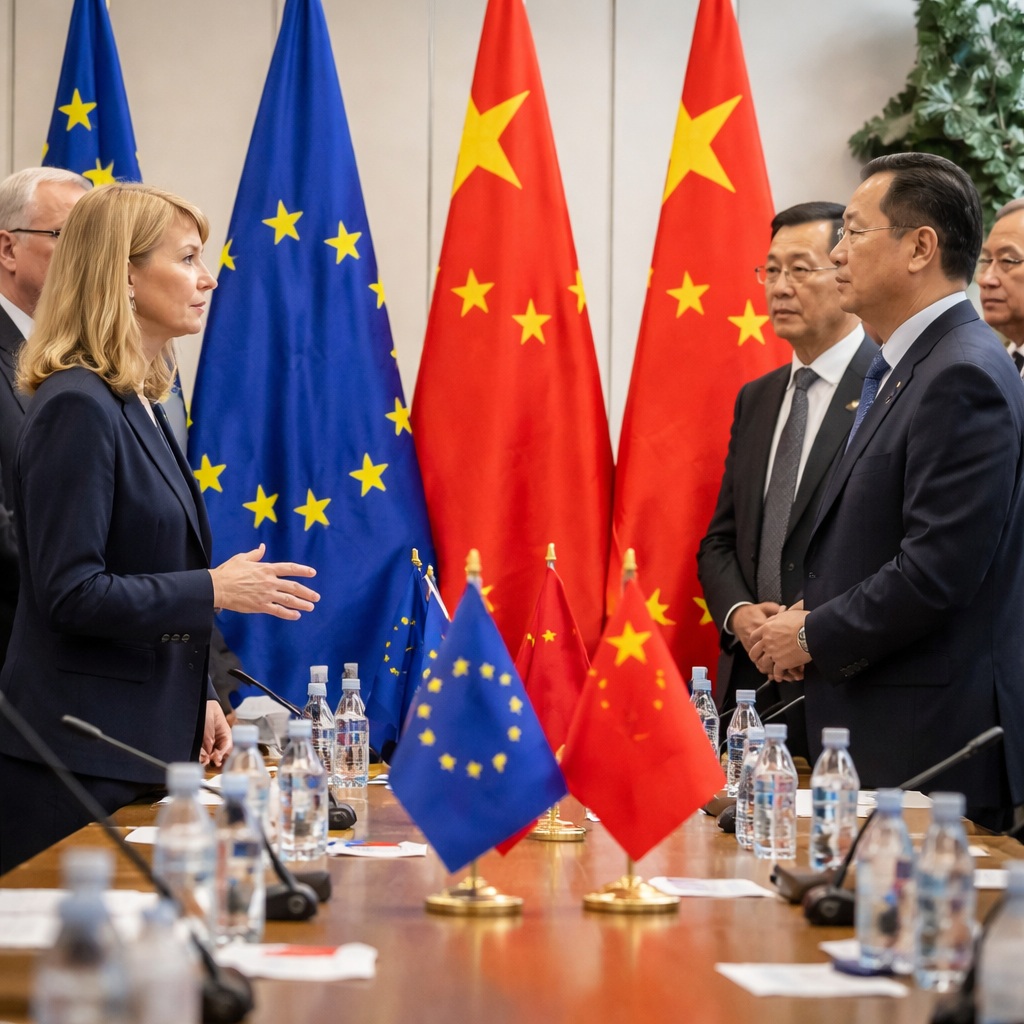

As the year draws to a close, a senior European Union official has issued a pointed warning about the nature of China’s economic engagement with the world. According to the EU’s foreign policy chief, Beijing’s vast network of trade, investment, and infrastructure links should not be viewed as neutral commerce alone, but as instruments that can be mobilized for political leverage.

The remarks reflect a broader reassessment underway in European capitals, where policymakers are increasingly skeptical that economic interdependence automatically produces stability. Instead, they argue, it can generate new forms of dependence—dependencies that may be activated in moments of diplomatic friction.

At the center of the warning is the idea that market access, supply chains, and financing have become tools of statecraft. Chinese companies, many with close ties to the state, operate across strategic sectors ranging from energy and transport to digital infrastructure. When disputes arise, European officials fear that these connections could be used to exert pressure, quietly but effectively.

The EU’s top diplomat framed the issue as one that extends beyond tariffs and balance sheets. Economic relationships, she suggested, are increasingly inseparable from questions of sovereignty, security, and political alignment. This perspective marks a significant evolution from earlier decades, when globalization was widely seen as a depoliticizing force.

European businesses have long benefited from access to Chinese markets, just as China has gained from European technology, brands, and consumers. But recent experiences—such as sudden regulatory shifts, informal trade barriers, or selective enforcement—have fueled concern that economic openness may be asymmetrical. In Brussels, this has prompted calls for what officials describe as “de-risking” rather than full decoupling.

The warning also resonates with partners beyond Europe. Governments in Asia, Africa, and Latin America have similarly grappled with the implications of deep economic ties to China. Infrastructure projects and loans have delivered tangible development gains, but they have also raised questions about long-term dependency and political influence.

What makes the EU’s message notable is its timing and tone. Rather than framing the issue as a clash of ideologies, the statement emphasizes pragmatism. Europe, officials insist, is not seeking confrontation. Instead, it aims to ensure that economic cooperation does not come at the expense of political autonomy.

This stance underscores a shifting geopolitical landscape in which power is exercised less through military alliances alone and more through networks of trade, finance, and technology. In this environment, the boundaries between economics and politics are increasingly blurred.

As the world prepares to turn the page on the year, the EU’s warning serves as a reminder that globalization is entering a more contested phase. Economic ties remain vital, but they are no longer assumed to be benign. For policymakers, the challenge ahead lies in balancing openness with resilience—keeping markets connected while guarding against their use as instruments of coercion.

The debate is unlikely to fade as the new year begins. Instead, it is set to define how nations navigate cooperation and competition in an era where influence often travels along supply chains rather than battle lines.