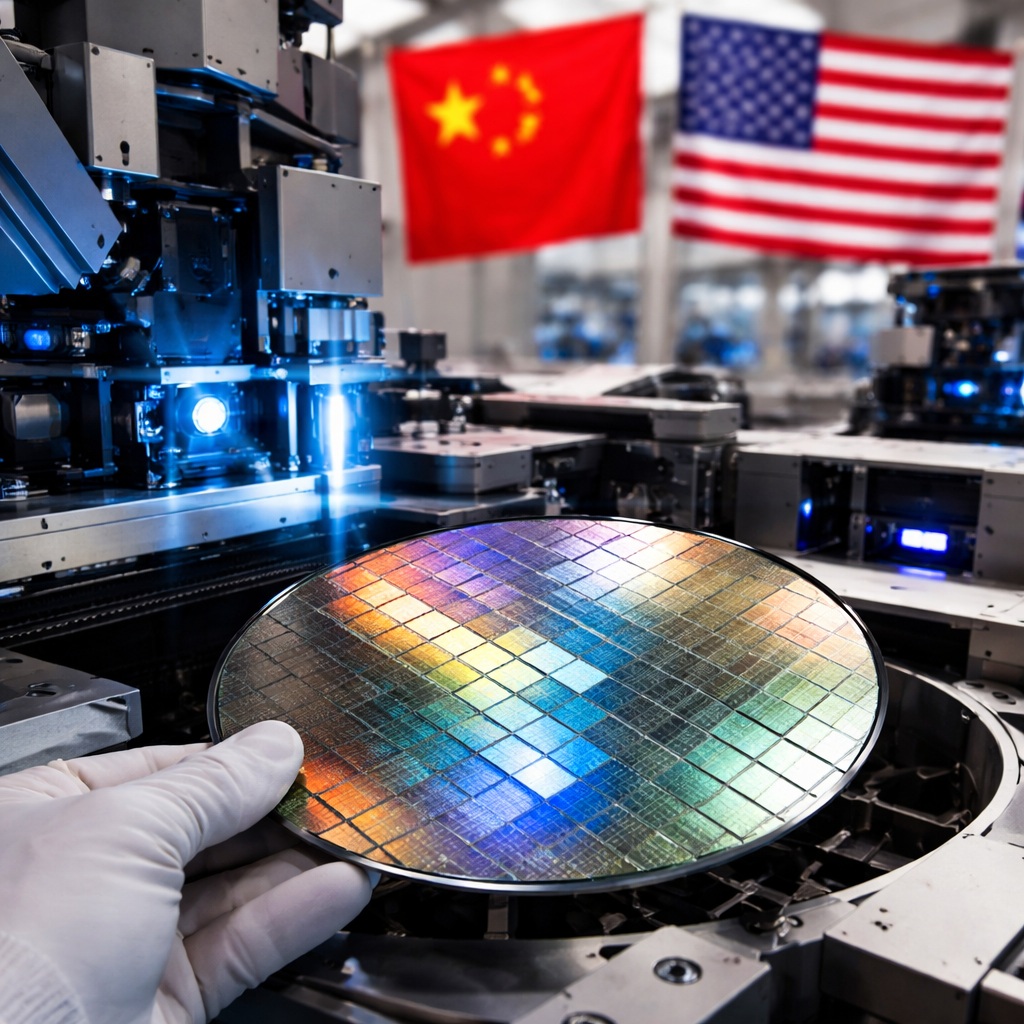

A quiet approval reshapes export controls, signaling a pragmatic turn in U.S.–China tech negotiations as the semiconductor supply chain adapts

By early January, Washington signaled a calibrated shift in its approach to semiconductor export controls, approving an annual license that allows Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to import certain U.S.-origin chipmaking tools into its operations in China for the coming year. The decision, disclosed by officials familiar with the matter, underscores a nuanced balancing act between national security concerns and the realities of a deeply interconnected global technology supply chain.

The license grants TSMC the ability to maintain and operate advanced manufacturing equipment sourced from American suppliers at its China-based facilities. While the approval does not represent a wholesale rollback of export controls imposed over recent years, it reflects a more flexible, case-by-case approach that has increasingly defined Washington’s technology policy toward Beijing.

At its core, the move acknowledges a practical dilemma. Semiconductors sit at the heart of modern economies, powering everything from consumer electronics to industrial automation and defense systems. Restrictive policies designed to limit China’s access to cutting-edge chip technology have, at times, strained alliances and disrupted multinational firms whose operations span borders and regulatory regimes.

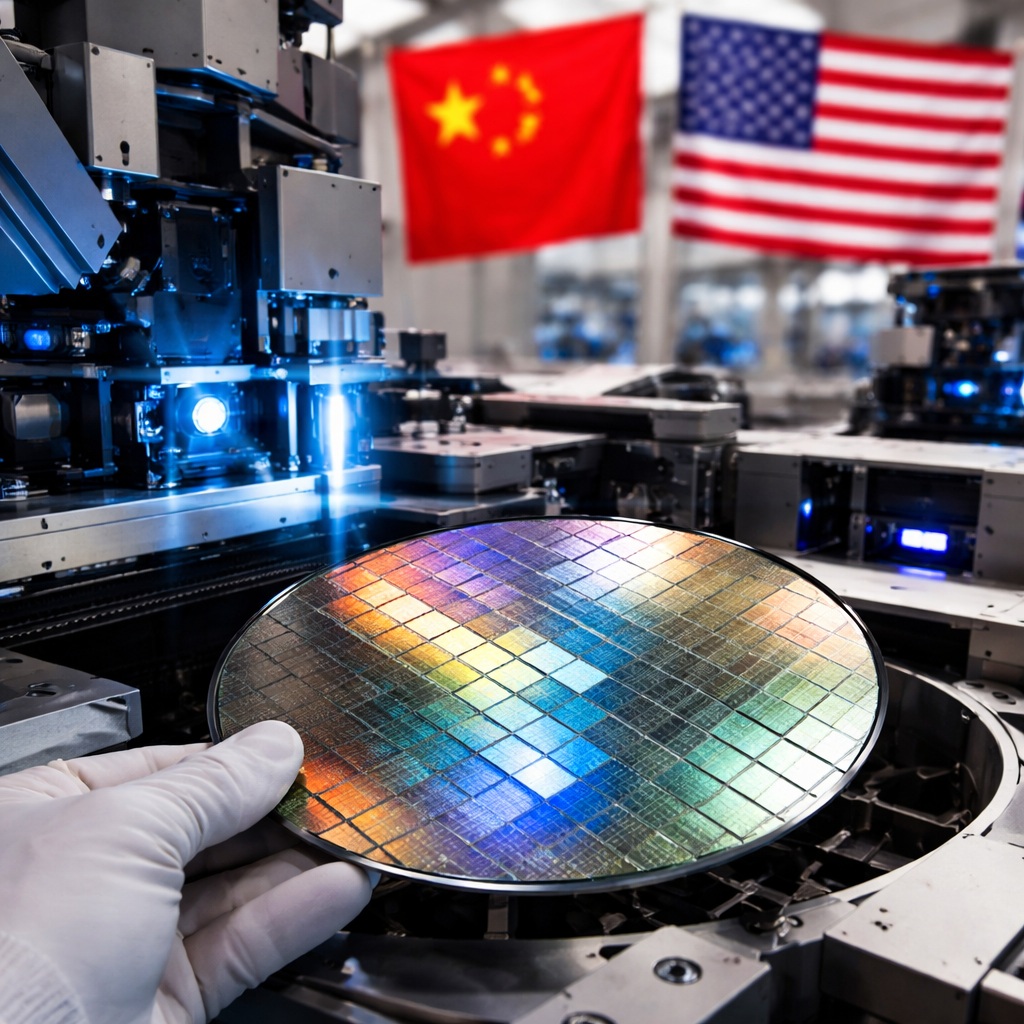

According to officials, the annual nature of the license is deliberate. By limiting approval to a defined period, the U.S. government preserves leverage while allowing companies to plan operations with a measure of predictability. Each renewal becomes a checkpoint, offering Washington an opportunity to reassess geopolitical conditions, compliance behavior, and technological developments before extending or revising permissions.

For TSMC, the world’s most influential contract chipmaker, the license provides operational continuity in a critical market. The company’s presence in China, focused largely on mature-node manufacturing rather than the most advanced processes, has long been a point of scrutiny in Washington. U.S. policymakers have sought to ensure that American technology does not directly enable breakthroughs that could bolster China’s military or surveillance capabilities.

Industry analysts note that the tools covered by the license are generally used for maintaining existing production lines rather than enabling next-generation chips. Still, even incremental allowances can have outsized effects in an industry where downtime is costly and margins depend on scale and efficiency.

“This is not a dramatic thaw, but it is a signal,” said one semiconductor policy expert. “It shows that Washington is willing to differentiate between existential security risks and the operational needs of global firms.”

The decision also reflects ongoing dialogue between the United States and China aimed at stabilizing their broader economic relationship. While tensions remain high over trade, security, and technology leadership, both sides have expressed interest in preventing further escalation that could fracture global markets.

For Beijing, the license is a reminder of continued dependence on foreign technology, even as it accelerates efforts to build a self-sufficient semiconductor ecosystem. For Washington, it is an acknowledgment that absolute decoupling is neither feasible nor necessarily desirable in the near term.

U.S. officials emphasize that the approval does not alter the strategic objective of protecting sensitive technologies. Export controls on the most advanced chipmaking equipment and designs remain firmly in place. The license, they argue, is a targeted instrument, not a policy reversal.

The ripple effects extend beyond bilateral relations. Semiconductor supply chains stretch across Asia, Europe, and North America, with equipment, materials, and expertise flowing through a complex web of partnerships. Sudden regulatory shifts can reverberate through this system, affecting prices, investment decisions, and innovation timelines.

In recent months, allied governments have pressed Washington for clarity and consistency in its export control regime. The annual license framework may offer a template, combining oversight with adaptability. By tying permissions to regular reviews, the U.S. can coordinate more closely with partners while responding to fast-moving technological change.

For companies across the sector, the message is mixed but manageable. Compliance burdens remain heavy, and uncertainty persists, but the door to pragmatic accommodation is not closed. Firms are expected to invest more in compliance infrastructure, transparency, and dialogue with regulators to navigate an environment where policy and production are increasingly intertwined.

As the year opens, the license stands as a modest yet meaningful adjustment in the semiconductor standoff. It reflects an understanding that technology policy, like the chips it governs, is built layer by layer—etched by security concerns, economic imperatives, and the enduring reality of global interdependence.