A senior European voice signals a structural shift in transatlantic relations as Brussels recalibrates its strategic priorities amid global fragmentation.

As winter settles over Brussels, a quiet but consequential reassessment is underway inside the European Union’s political machinery. Europe, according to a senior EU official speaking on background, is no longer Washington’s “centre of gravity” — a phrase that once captured the unquestioned centrality of the transatlantic alliance in Western strategy. The remark, delivered without theatrics, reflects a deeper and more durable shift in how Europe sees its place in the world and how it believes the United States now orders its priorities.

For decades after the Cold War, Europe occupied a privileged position in American foreign policy. NATO expansion, economic integration, and shared democratic narratives anchored the relationship. Today, EU officials increasingly describe that era as structurally over. The change, they insist, is not about hostility or rupture, but about gravity — where power, attention, and resources naturally pull.

“The United States has not abandoned Europe,” the official said. “But it no longer orbits around it.”

A world reordered

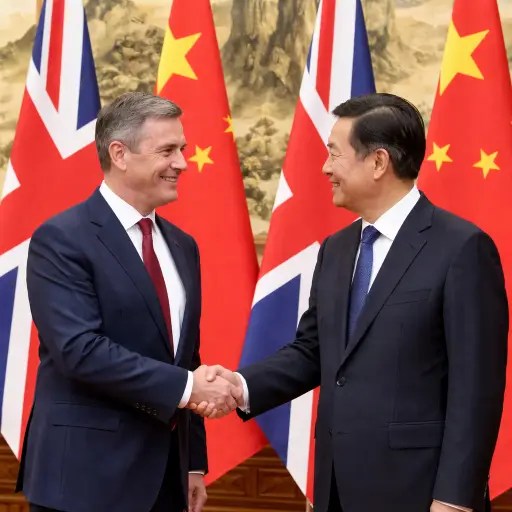

At the heart of this recalibration lies a global system marked by fragmentation and competition. Washington’s strategic focus has widened toward the Indo-Pacific, where China’s economic scale and military reach demand sustained attention. Simultaneously, crises in the Middle East, technological rivalry, and domestic political pressures have stretched U.S. bandwidth.

From a European perspective, the implication is clear: reliance on American leadership can no longer be the default assumption. This realization has accelerated debates in Brussels about strategic autonomy — a concept once dismissed by critics as aspirational or even disloyal to NATO, but now treated as pragmatic necessity.

European diplomats say the shift has been gradual, but unmistakable. U.S. engagement remains decisive in areas such as deterrence and intelligence, yet it is increasingly selective and transactional. The old reflex of automatic alignment is giving way to a more conditional partnership, shaped by converging interests rather than inherited habits.

Security without illusions

Nowhere is this evolution more visible than in security policy. The war on Europe’s eastern flank has reinforced the importance of collective defense, but it has also exposed asymmetries. While American support has been critical, European leaders have acknowledged gaps in industrial capacity, command structures, and long-term planning.

An EU defense official described the mood as “sobering, not panicked.” The lesson drawn is not that the United States is unreliable, but that Europe must be more capable of acting when U.S. priorities lie elsewhere.

This has translated into renewed investment in defense production, joint procurement, and military mobility within the EU. Long-stalled initiatives are being reframed less as symbolic gestures and more as tools for resilience. The political language has shifted as well: autonomy is increasingly paired with responsibility.

Economic fault lines

Beyond security, economic relations have also contributed to Europe’s reassessment. Trade disputes, industrial subsidies, and divergent regulatory philosophies have complicated what was once portrayed as a seamless economic partnership. European policymakers point to supply chain disruptions and competition over green and digital technologies as signs of a more competitive transatlantic landscape.

In Washington, industrial policy is openly framed as a matter of national security. In Brussels, similar logic is gaining ground. The result is not decoupling, but a more guarded form of interdependence.

“Partnership now requires constant negotiation,” said one EU trade official. “Trust is still there, but it is no longer unconditional.”

Political psychology

The shift away from seeing Europe as Washington’s centre of gravity is also psychological. Younger European leaders, shaped by crises ranging from financial instability to pandemics and war, are less inclined to view the transatlantic relationship as the sole anchor of European strategy. They speak more comfortably about multipolarity, hedging, and regional responsibility.

This generational change is mirrored in public opinion. While support for cooperation with the United States remains strong, expectations have become more modest. The idea that Europe must be able to stand on its own — economically, militarily, and technologically — now commands broad political consensus across much of the bloc.

Not a divorce

EU officials are careful to stress what this shift is not. It is not a rejection of NATO, nor a turn toward anti-Americanism. The United States remains Europe’s closest ally, and cooperation continues across intelligence, defense, and diplomacy.

But the language of inevitability has faded. Alliance is no longer assumed to be the organizing principle of global order; it is one pillar among several.

In this sense, the official’s remark about Europe no longer being Washington’s centre of gravity captures a moment of strategic adulthood. Europe is adjusting to a world in which attention is contested, power is diffuse, and guarantees are less automatic.

As one senior diplomat put it, “We are not moving away from the United States. We are moving toward a more realistic understanding of ourselves.”

That realism, EU leaders argue, may ultimately strengthen the transatlantic bond — not by restoring the past, but by redefining partnership for a more uncertain world.