UK prime minister opens a long‑awaited China visit, urging businesses to seize opportunity while guarding national security in a fractured global landscape.

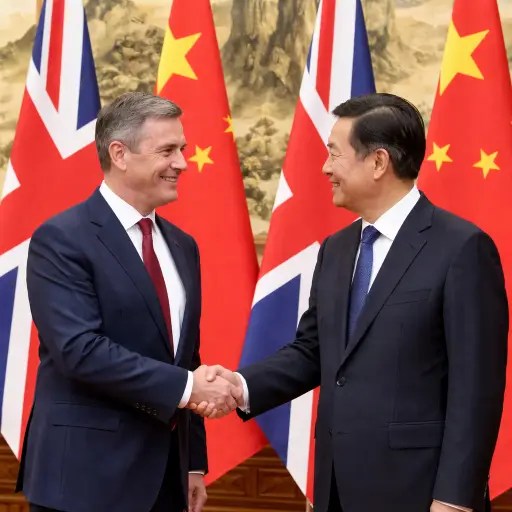

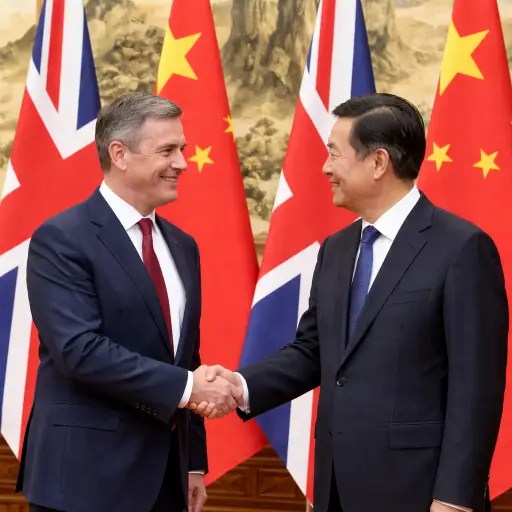

The British prime minister arrived in China this week on a trip heavy with symbolism and hedged with caution, the first visit by a UK leader in nearly a decade and a test of whether London can reset a relationship long frozen by mistrust.

Keir Starmer’s message to British companies travelling with him is deliberately dual‑track: China remains too large to ignore, but too complex to embrace without guardrails. In meetings with senior Chinese leaders and executives, the prime minister is expected to promote trade, investment and climate cooperation, while underscoring Britain’s red lines on security, technology and democratic values.

The visit comes at a moment when Western relations with Beijing are strained by disputes over trade practices, cyber security, human rights and geopolitical rivalry. Against that backdrop, Starmer is pitching what aides describe as a “pragmatic engagement” — neither the cheerleading of an earlier era nor the blanket suspicion that followed years of diplomatic chill.

For UK exporters, the lure is obvious. China remains a vast market for advanced manufacturing, life sciences, financial services and green technology, sectors the government sees as central to domestic growth. Business leaders accompanying the delegation say demand is returning unevenly but decisively, and that absence carries its own risks in a competitive global economy.

Yet security concerns hang over every conversation. British officials are wary of over‑reliance on Chinese supply chains, sensitive data exposure and the strategic implications of Chinese investment in critical infrastructure. Starmer has stressed that openness will be matched by scrutiny, with tougher investment screening and clearer rules for technology partnerships.

In Beijing, Chinese officials have signalled interest in stabilising ties with Europe as relations with Washington remain volatile. They are expected to press for fewer restrictions on trade and a more independent European posture. Whether that translates into concrete concessions remains uncertain.

Diplomatically, the trip is calibrated to avoid grand gestures. There are no sweeping agreements expected, but incremental steps: dialogue mechanisms restarted, business forums reopened, and cooperation explored on climate finance and public health. The tone is cautious, the ambition contained.

At home, the visit carries political risk. Critics argue that engagement rewards behaviour they see as coercive abroad and repressive at home. Supporters counter that isolation has yielded little, and that Britain needs a clear‑eyed strategy that combines economic realism with national resilience.

Starmer’s challenge is to convince both audiences — British voters and Chinese counterparts — that the UK can trade without compromising its security or values. The success of the visit will be measured less by headlines than by whether it establishes a workable rhythm for a relationship that has been stuck between opportunity and anxiety.

As the delegation moves from formal talks to factory floors and boardrooms, the prime minister’s balancing act is on full display. In today’s fractured world, engagement itself has become a statement — and caution, a policy.