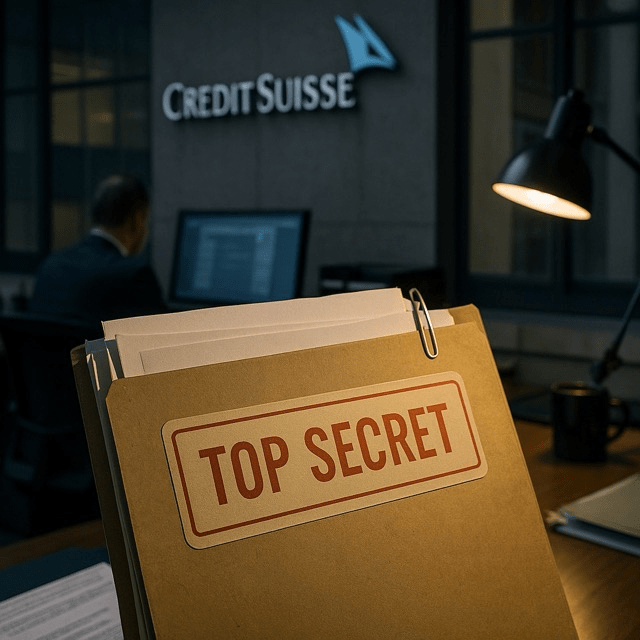

How Leaked Documents Exposed Risky Deals and Political Connections in the Supply Chain Finance Scandal

The downfall of Greensill Capital in early 2021 sent shockwaves across global finance, yet buried beneath headlines was a trove of secret Credit Suisse files that shed light on covert intelligence gathering, political lobbying, and anonymous whistleblower tips. Joint investigations by the Financial Times and consortium partners have unearthed internal documents, emails, and risk assessments compiled by Credit Suisse’s risk and compliance teams, revealing how the Swiss bank’s close ties with Greensill obscured mounting vulnerabilities and fostered a culture of silence.

Central to the scandal were emails exchanged between senior executives at Credit Suisse and Greensill founder Lex Greensill. These communications, marked as “confidential” and “highly sensitive,” detailed bespoke financing arrangements for high-profile clients, while internal risk reports flagged exponential growth in exposure to supply chain receivables. Yet despite memos alerting risk officers to potential conflicts—such as Greensill’s dual role as financier and consultant—approvals for billions of dollars in credit facilities pressed forward, often expedited by pressure from top management keen to reap lucrative fees.

The files also expose a sophisticated network of political influence. In the UK, Greensill leveraged connections to former Prime Minister David Cameron, who acted as an adviser to the firm. Cameron’s staunch lobbying of Treasury and Health Department officials on Greensill’s behalf was documented in internal summaries, with government sources noting repeated “anonymized tips” supplied by Credit Suisse personnel about the scheme’s benefits to local industries. Leaked minutes show officials privately questioning the propriety of these backchannel communications, though no formal investigation ensued at the time.

Anonymous whistleblowers played a pivotal role in bringing the hidden risks to light. A Credit Suisse compliance officer, who remains unnamed in publicly released documents, submitted an urgent tip via the bank’s internal reporting hotline in late 2020. The memo warned of “unprecedented concentration” in supply chain assets and cited “undisclosed guarantees” that Greensill arranged personally. Despite regulatory mandates to follow up on such tips, internal audit logs reveal that the complaint was shelved pending legal review, effectively muting alarm bells until widespread defaults triggered the firm’s collapse.

Further revelations emerged from credit memoranda describing how Credit Suisse structured investment vehicles for wealthy clients, touting yields of 8–12% backed by short-term commercial receivables. The files illustrate how stress tests—designed to model delayed payments or client insolvencies—were selectively applied, with assumptions favoring optimistic recovery rates. In one presentation, a slide titled “Tail Risk Scenario” was annotated with management comments instructing analysts to “dilute severity” before board review, raising questions about the integrity of risk disclosures.

The leak of these secret files has reignited debates over the adequacy of banking oversight and the role of “shadow banking” in the broader financial system. Regulators in Switzerland and the UK have launched inquiries into Credit Suisse’s governance lapses and Greensill’s licensing arrangements, while European parliamentarians have called for enhanced whistleblower protections and greater transparency in political lobbying. The scandal has also prompted Credit Suisse to overhaul its compliance framework, including the establishment of an independent risk committee with mandatory rotation of members.

The political ramifications extend beyond corporate boardrooms. In Canberra, Australian officials are scrutinizing the intertwined interests of Greensill and local steel industry clients who benefited from supply chain financing. Similarly, in Japan, parliamentary questions have probed whether financial regulators were misled by anonymized tips orchestrated through third parties. In each jurisdiction, the central question remains: how did a network of spies, lies, and whispered warnings evade detection until the final collapse?

As the fallout continues, industry experts emphasize the need for systemic reform. Proposals include mandatory real-time reporting of non-bank lending exposures, fortified “audit trails” for anonymous tips to ensure follow-up, and rigorous firewalls between advisory and financing divisions. For investors and policymakers, the Credit Suisse–Greensill files serve as a stark reminder that behind polished balance sheets can lie perilous commitments, shielded by secrecy and amplified by political influence.

In the end, the Greensill saga underscores a fundamental truth: financial markets thrive on trust, yet too often thrive on half-truths. The revelation of these covert files may represent a watershed moment in restoring transparency, accountability, and the rule of law in global finance—and serve as a warning that in the age of anonymous tips, those who ignore the whispers do so at their peril.